A recent release by Avalanche Press looks like it has a lot to offer the board gamer for the Italo-Ethiopian War. The game system (which this author hasn’t played) appears to be a very mature system as it has been utilised for many previous titles. This only adds to the completeness and ease of play that the Conquest of Ethiopia title is likely to offer.

A recent release by Avalanche Press looks like it has a lot to offer the board gamer for the Italo-Ethiopian War. The game system (which this author hasn’t played) appears to be a very mature system as it has been utilised for many previous titles. This only adds to the completeness and ease of play that the Conquest of Ethiopia title is likely to offer.

The publishers webpage gives a good deal of support material and a complete listing of the scenarios included. These scenarios highlight the many possible actions that can be gamed during the war. As usual there is a BoardGameGeek support page and the rules for the game can found online as well.

There isn’t much to add to the publisher’s webpage other than to suggest that using appropriate British and French counters would allow a gamer to use the Conquest of Ethiopia as a means to explore The Abyssinian Crisis through this medium, which has alot of potential. To that end I have included the scenarios below to show just how diverse the actions were in this conflict and to highlight that it has much to offer the miniatures player as a gaming period.

.

Scenario List for Conquest of Ethiopia

The following notes and previews of scenarios in the Conquest of Ethiopia come from the Avalanche Press website. They are put here for future reference just in case they are subsequently not made available online. They offer ideas, thoughts and lots of scenario inspiration for miniatures gamers, so have worth beyond being simple scenario previews for the board game. Indeed, it can be seen just how much depth the board game has within its covers and the effort put in by the game designers. The Abyssinian Crisis web blog thanks Avalanche Press for the board game and providing such excellent support material to go with it.

INTRODUCTION

While the Italian invasion of Ethiopia is rightly seen as a prelude to World War II, the early fighting usually represented the clash of well-armed tribes serving either the Italians or the Ethiopian central government. This sort of irregular warfare rarely involved much artillery, and though the Italians at times applied liberal air support the decisions usually came down to fierce hand-to-hand fighting.

When it’s discussed in Western historical literature (at least outside of Italy) the Second Italo-Ethiopian War is often portrayed as a parable of the modern crushing the traditional. Much is made of the Italian advantages in technology, with emphasis on aircraft, mechanized vehicles and advanced weaponry.

Like a lot of superficial assessments, that isn’t exactly true. The Italians had very definite technological advantages in what modern militaries call C3I: command, control, communications and intelligence. Their command of the air and well-developed system for gathering and interpreting aerial reconnaissance photos and reports gave Italian commanders a wealth of data about enemy troop movements that no army had ever known up to that point. With their radio network, they could instantly update orders to their subordinates where the Ethiopian leaders had to rely on messengers on foot and horseback.

The Italians also went to war with a far more efficient logistics infrastructure than that of the Ethiopians. Italian troops could be assured of having food, water and ammunition – sometimes even dropped by aircraft. The Ethiopians relied on herds of livestock driven behind their massive armies and subject to air attack. Had they managed to defeat the Italians in battle, keeping their troops in the field would have become very difficult had the war gone on much longer.

But on the tactical level, the gap is not nearly as great. The Ethiopian regulars, and many irregulars, carried modern rifles – many of them Austrian-made Mannlichers bought from Italy after the First World War. Ethiopian infantry firepower wasn’t far behind that of the Italians, though they had fewer machine guns. The Italians had much more artillery, but still very little by the standards of World War II.

It’s one thing to tell about the elements of a historical event, but when it’s done right, a historical game designer can show why an event unfolded as it did. With Conquest of Ethiopia, Lorenzo Striuli and Ottavio Ricchi did an excellent job showing the tactical reality of this relatively little-known war. The Italians usually deploy more leaders, as befits a more educated society, but the Ethiopians almost always have higher morale and often better initiative. I believe you can learn a lot about this conflict by playing the scenarios designed by Lorenzo and Ottavio.

.

SCENARIO ONE

Initial Troubles

4 October 1935

The Seraè Banda continued their advance, but their pace slowed with the increasingly difficult terrain. The following day they encountered the Daro Taclè fort manned by approximately 100 Ethiopian Imperial Irregulars, reinforced with a few machine guns.

Conclusion

After the loss of Tenente Morgantini (the first Italian officer to die in the conflict), the Dubat of the Seraè Banda retreated with heavy losses (16 dead, 15 wounded, and 16 missing). The following day, at dawn, III Battalion Indigeni, supported by two light tanks, smashed the fort’s garrison with very few losses (it’s possible some of the Ethiopians retreated during the night). In the following days, the Italians and Ethiopians fought several more clashes that mostly resulted in Italian victories as their artillery often shattered the enemy well before the opposing troops came to blows.

Notes

Once again the Italian screen of lightly-armed and fast-moving Bande run into Ethiopian opposition. This one’s just a small scenario; the Ethiopians are outnumbered pretty badly but they have a hilltop fort and pretty stout morale. This is a fine intro scenario, which is why it appears slightly out of chronological order.

SCENARIO TWO

Prelude: The Wal Wal Incident

6 December 1934

On the Ogaden plateau, in a disputed border area between the colony of Italian Somaliland and the Ethiopian province of Hararshe, Italian colonial troops (Dubats) and Ethiopian regulars and mercenaries conducted several days of show-of-force activities trying to intimidate each other. After some weeks of threat and counter-threat, shooting broke out, with each side blaming the other for starting hostilities.

On the Ogaden plateau, in a disputed border area between the colony of Italian Somaliland and the Ethiopian province of Hararshe, Italian colonial troops (Dubats) and Ethiopian regulars and mercenaries conducted several days of show-of-force activities trying to intimidate each other. After some weeks of threat and counter-threat, shooting broke out, with each side blaming the other for starting hostilities.

Conclusion

The outnumbered colonial Dubats fought bravely, assisted by a small number of Italian tanks and armored cars whose crews fought with fanatical zeal. The Ethiopian advance on the fort was thrown back, and during the night a lone L3/35 entered the Ethiopian cantonment, harassing the enemy until the following morning when it ran low on ammunition. The next day the Ethiopian Imperial troops retreated, leaving the mercenaries behind. Several months later this event served as the casus belli for the Italian invasion of Ethiopia.

Notes

This one’s a kind of complicated scenario, so I shuffled it slightly further back in the order of appearance. That said, it’s a big scenario pretty much bursting with coolness: fanatic Italian tankers, Ethiopian mercenaries, Somali Dubats.

SCENARIO THREE

The First Clash: Ramà

3 October 1935

In the first phase of Italian General Emilio De Bono’s offensive, only the II Corps experienced any real resistance, and several local Ethiopian leaders seriously considered defecting to the Italian side. The remaining local commanders opted to follow Emperor Haile Selassie’s orders to delay the Italian advance in order to buy time for the slow general mobilization of the country. Later, they all united to strike the Italians. One the first notable clashes between Italian and Ethiopian troops came at Ramà in the province of Tigray.

Conclusion

After a brief pause, the Seraè Banda – irregulars in Italian service – smashed the Ethiopian resistance with the support of two light tanks. As one of the most forward-deployed units of II Corps it continued to lead the advance, making use of its local knowledge.

Notes

It’s another Bande battle (“Bande” are the troops, “Banda” is a unit of them), Eritrean irregulars in Italian service. The Italians are on the attack spearheaded by some very weak armor support – but the Ethiopians have no anti-tank weapons. This scenario also introduces Ambà, the Devil’s-Tower-like formations of Ethiopia that have their own special climbing rules.

SCENARIO FOUR

Passo Gashorchè

5 November 1935

During the advance toward Adowa, the II Corps encountered several hundred soldiers of Ras Sejum (Ras is an aristocratic title similar to Duke). The Ras deployed his men only to slow the Italian advance, in accordance with Emperor Haile Selassie I’s orders to reserve most of his forces for the planned general counterattack. However, this defensive stance affronted the innate bravery of the Ethiopians, and led to occasional undesired heavy engagements when forces disregarded the Emperor’s strategic priorities.

During the advance toward Adowa, the II Corps encountered several hundred soldiers of Ras Sejum (Ras is an aristocratic title similar to Duke). The Ras deployed his men only to slow the Italian advance, in accordance with Emperor Haile Selassie I’s orders to reserve most of his forces for the planned general counterattack. However, this defensive stance affronted the innate bravery of the Ethiopians, and led to occasional undesired heavy engagements when forces disregarded the Emperor’s strategic priorities.

Conclusion

The Ethiopians paid for their bravery with severe losses, but managed to stop this small sector of the Italian advance for almost a day. Colonel Fedor Evgenievich Konovaloff, a White Russian officer serving with the Ethiopian army, heard survivors describe the 70th Tuscan Infantry’s assault on their position as utterly fearless, with no regard for their own injured companions.

Notes

Now the Italian regulars, both Metropolitan and Colonial, make their first appearance. They have a slight morale advantage and a definite edge in artillery, and they’re going to need them as they’re attacking a much larger Ethiopian force.

SCENARIO FIVE

Surprise at Mount Gundi

5 November 1935

During the second phase of General Emilio De Bono’s advance toward Macallè, several Eritrean Indigeni battalions patrolled the gaps between his major corps columns to secure the surrounding areas from the emerging guerrilla threat. During one of these actions, Ethiopian forces attacked two Indigeni battalions as they were encamping for the night.

Conclusion

After a fast-moving skirmish, the Ethiopians irregular retreated. They lost about a third of their men, including prisoners, but inflicted a morale-boosting slap to the Italians. In this phase of the conflict these clearing actions played a significant role in assuring security for De Bono’s forces.

Note

This is a short scenario, a close-quarters melee in the last hours of daylight. The Ethiopians have surprisingly high morale, but the Italians have numbers and firepower on their side. Numbers and firepower are good things to have in a fight.

SCENARIO SIX

Ambush at Azbi

12 November 1935

During the march toward Macallè, a Colonial troop column received the task to cover the right flank of the Eritrean Corps’ advance. During their march along the dry bed of the Enda River they ran headlong into an ambush set by the Degiac Cassa Sebhat force, equipped with several heavy machine guns. This would be the last major engagement before Marshal Badoglio replaced De Bono.

During the march toward Macallè, a Colonial troop column received the task to cover the right flank of the Eritrean Corps’ advance. During their march along the dry bed of the Enda River they ran headlong into an ambush set by the Degiac Cassa Sebhat force, equipped with several heavy machine guns. This would be the last major engagement before Marshal Badoglio replaced De Bono.

Conclusion

The Ethiopians managed to stop the enemy column for an entire day. Both sides suffered heavy losses, and during the night Degiac Cassa Sebhat retreated his forces. The following day the Italian column sat in place suffering from logistical difficulties and recovering from the battle. However, the Regia Aeronautica managed to perform one of the first parachute re-supply operations in military history. Another day passed, and the column resumed its march.

Notes

The Ethiopians have set up a roadblock (including a small ambush), and it’s up to the Italians to bop their way past. Eventually they’ll have numbers and firepower on their side, but morale is with the Ethiopians.

SCENARIO SEVEN

Graziani’s War: Border Corrections

18 October 1935

Generale Rodolfo Graziani commanded the southern front of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Intended to be a defensive front, Graziani proposed other ideas and received permission from Rome to move offensively. The first actions on the southern front (the Somali front, where the Italians had to face some of the finest of Hailè Salassiè’s troops) were called “border corrections.” The Regia Aeronautica carried out almost all of the initial attacks, employing bombing and strafing runs that forced some Ethiopian forts and garrisons to surrender. The first real occasion Italian troops and the allied Sultan Olol Dinle’s private army had for measuring themselves against the brave enemy occurred on the 18th of October.

Conclusion

The heavy Italian air support combined with the mud proved very effective in inhibiting the Ethiopian forces’ initiative. However, they displayed their bravery, managing to damage six Italian aircraft and heavily harass the Bande’s advance throughout the day. Nevertheless, as night fell the Italian colonial troops forced the Ethiopians to retreat from the fort. However, Hamed Badil’s mercenaries resisted in the Gilde village until the following morning, holding up Olol Dinle’s dismounted cavalry. Not until II Bande Group pitched in did the standoff resolve itself. Badil, a cousin and long-time rival of Olol Dinle, managed to escape, but Dinle captured him a few days later. Dinle offered Badil a sumptuous tent, a fine dinner, and women for the evening. Later that night Badil’s own brother strangled him on Olol Dinle’s orders.

Notes

We shift to the Somali front, where the Italians are also screening their advance with swarms of irregular Bande plus some tough Somali warriors from a semi-independent allied sultanate. The Italians have numbers and initiative plus a lot of airpower; the Ethiopians have slightly better morale plus they have a fort.

SCENARIO EIGHT

Graziani’s War: A Sorrowful Victory

10 November 1935

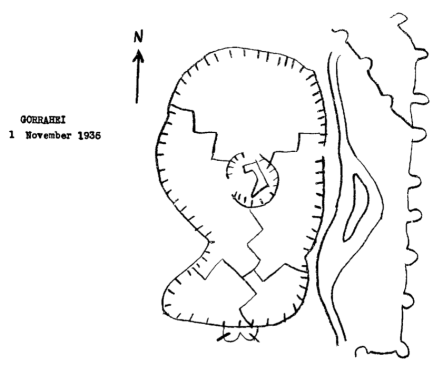

Heavy aerial attacks forced the unanticipated surrender of the Gorrahei Fort without any fighting against the Italian ground troops. The Maletti Column en route to take the fort found itself “unemployed,” and headquarters changed their mission to a reconnaissance in force. After a few successful minor engagements, Col. Pietro Maletti’s men met a strong, well-equipped detachment of enemy forces. The Ethiopians deployed a few of their 20 handcrafted armored cars (partially manned by foreign military advisors) in the ensuing battle.

Heavy aerial attacks forced the unanticipated surrender of the Gorrahei Fort without any fighting against the Italian ground troops. The Maletti Column en route to take the fort found itself “unemployed,” and headquarters changed their mission to a reconnaissance in force. After a few successful minor engagements, Col. Pietro Maletti’s men met a strong, well-equipped detachment of enemy forces. The Ethiopians deployed a few of their 20 handcrafted armored cars (partially manned by foreign military advisors) in the ensuing battle.

Conclusion

The Italian armored force managed to disrupt their Ethiopian counterparts. Then, with the Dubats’ help, they smashed the enemy defensive points. The Ethiopian main force retreated to the eastern hill south of the wadi, leaving a handful of machine guns to provide covering fire. Then the tide of fortune turned. One L3/35 tank bogged down in a mud pond just in front of a Hotchkiss machine gun reputedly manned by Guangual Kolasè in person. All the efforts to recover the crew were fruitless, and the other two tanks broke down under fire trying to tow out the first tank. The Dubats tried several times to put the enemy machine gun out of action and save the isolated and wounded tank crews, but enemy snipers and machine gun fire killed or wounded enough men to drive them off. After several hours, a prisoner warned Maletti of the imminent arrival of massive Ethiopian reinforcements (a fabrication). Maletti believed the lie, or perhaps he just wanted an excuse to retreat his exhausted and wounded Dubat who had suffered 60 percent casualties.

Maletti intended to come back during the night or the following day and rescue the isolated crews. However, as soon as the column left those unfortunate soldiers were captured by the Ethiopians and tortured. When Emperor Hailè Salassiè arrived in the area three days later for an inspection of the local commanders, he refused to spare the prisoners’ lives (as requested by some foreign advisors attached to his court). The condemned men spent several weeks in miserable conditions before finally being executed. Colonel Maletti survived this battle but would later die at the beginning of the 1940 British offensive in North Africa.

Notes

Tank battle! Well, what passes for a tank battle in the Italo-Ethiopian War anyway, as the Ethiopians send out their small force of armored cars (actually rebuilt trucks) to do battle with Italian armored cars and tankettes. Plus Bande. Always with the Bande. There aren’t a lot of anti-tank weapons on the board, and those that are present aren’t very potent, so it’s not exactly the Battle of Kursk, East African style.

SCENARIO NINE

Unfinished Symphony

15 December 1935

In contrast with the Marshal Badoglio’s anticipation of enemy actions pivoting on Macallè, the Ethiopian counterattack began with broad infiltrations across a wide area covering the Tembien and Scirè regions. Ras Immirù possessed a well-equipped and well-led force on the left wing, and his superb campaign would prove to be one of the best moments for the Ethiopian leaders. His infiltrations and consequent series of small successful engagements worried the strong Italian advanced detachment deployed on Tacazzè River. The commander decided it was prudent to retreat, but found the only available route blocked by the Ethiopians.

Conclusion

Major Luigi Criniti, commander of the Bande dell’Altopiano Group, launched his small fleet of L3/35 tanks in an attack without infantry support: a hopeless endeavor. The Ethiopians disabled all of them in brave close combat (placing big stones in the tracks, shooting throughout the sighting ports, setting fires on the engine gratings and so on). They also captured two tank crew prisoners who were treated well and survived the war. In return, Fitawrari Sciferra’s force suffered heavy losses, included the Sciferra himself. The Bande showed exceptional morale, probably sparked by knowledge that the Ethiopians would slaughter any who surrendered, and moved forward to support the disabled tanks. They found themselves encircled by pursuing Ethiopian units that had forced their retreat the previous day and chased them across the Mai Timchet ford. Realizing their encirclement, some of the Bande began to surrender, but were horrified when they realized that the Ethiopians did not understand or honor their hands-up gesture and began killing them. Criniti began to play his gramophone (Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony) and headed a bayonet assault to break the encirclement. Although injured twice, the Major and his men broke out and retreated rapidly toward Enda Salassiè, having lost over half their numbers.

Notes

A bayonet charge with symphonic accompaniment. Is there really anything else to say?

SCENARIO TEN

Ras Sejum’s Attack: Debra Ambà

18 December 1935

Although effective against fixed positions, the Italian air campaign proved unable to inhibit Ethiopian infiltration tactics, leading to sizable Ethiopian forces maneuvering against Italian positions. However, the Regia Aeronautica excelled at reconnaissance, alerting the Italian High Command so they could quickly dispatch strong reinforcements where needed. East of Ras Immirù’s forces, Ras Sejum began a series of violent attacks against a Blackshirt Group led by Console Generale Filippo Diamanti. The most important actions by Ras Sejum took place in the Abbi Addi area, with the first big attack carried out at Debra Ambà. Thanks to those eyes in the sky, Diamanti and his men were already in place.

Although effective against fixed positions, the Italian air campaign proved unable to inhibit Ethiopian infiltration tactics, leading to sizable Ethiopian forces maneuvering against Italian positions. However, the Regia Aeronautica excelled at reconnaissance, alerting the Italian High Command so they could quickly dispatch strong reinforcements where needed. East of Ras Immirù’s forces, Ras Sejum began a series of violent attacks against a Blackshirt Group led by Console Generale Filippo Diamanti. The most important actions by Ras Sejum took place in the Abbi Addi area, with the first big attack carried out at Debra Ambà. Thanks to those eyes in the sky, Diamanti and his men were already in place.

Conclusion

The day before the battle, the Ethiopians in the fort had sporadically harassed the Italians deployed on the Ambà with intense rifle fire. Feeling vulnerable, the Italians planned an attack to dislodge the Ethiopians and secure the area. A large detachment of Ethiopians intercepted the Italians as they approached Sicomoro Fort leading to a drawn-out ten-hour battle. The Ethiopians eventually retreated with heavy losses while inflicting only light casualties on the Italians thanks to weak firepower and a lack of many machine guns. Nevertheless, the action worried the Italian High Command who sent heavy reinforcements to the Abbi Addi area during the night and over the following days.

Notes

The Blackshirts make their first appearance, and they’re not half bad. The Ethiopians are inspired, with sky-high morale and not much more. The Blackshirts have an edge in firepower, even numbers and some artillery support.

SCENARIO ELEVEN

Blood on Ambà Tzellerè

22 December 1935

In the days following the clash at Debra Ambà the Ethiopian forces regrouped in the Abbi Addi area, increasing the pressure on the Italians deployed there. To relieve the threat, high command directed General Lorenzo Dalmazzo to take his 2nd Eritrean Brigade to reinforce them and assume command. Once situated, Dalmazzo decided to capture Ambà Tzellerè, the source of Ethiopians attacks on Abbi Addi.

Conclusion

The Eritreans fought bravely but bogged down in the woods and rough terrain. The Eritrean battalions suffered heavy casualties but displayed great heroism to save their artillery from destruction in episodes that saw the tubes fired over open sights at ranges of 50 meters! Just as the commander was considering calling off the attack, the II and IV Battalions of the MVSN began to arrive, bolstering the force. Ultimately, the Italians failed despite bombastic fascist propaganda claiming the Blackshirts successfully captured Ambà Tzellerè. On the contrary, both Badoglio and Diamanti admitted that the attack was a flop, and Badoglio blamed Dalmazzo for his decision to retreat just when the battle was nearly won. Of course Badoglio was not present so it’s hard to second guess the commander in the field (not that this often stopped Badoglio). In any case, the episode clinched the decision to abandon Addi Abbi after burning the village in spite, and the column retreated toward the Uarieu Pass to avoid the danger of encirclement posed by the converging Ras Sejum and Ras Cassa forces. Shortly thereafter the Italians began deploying chemical weapons against the Ethiopians.

Notes

This is a big scenario, with Blackshirts and Eritrean Colonials on the attack against a large mixed force of Ethiopians, who have the high ground and a significant morale advantage. As in most of the early scenarios in this game, the only artillery present is a handful of batteries the Italians bring onto the map.

SCENARIO TWELVE

Appiotti’s Column

25 December 1935

Attempting to regain the strategic initiative in the face of an increasingly aggressive Ethiopian attitude, the Italian High Command called on Maggiore Generale Giacomo Appiotti, a 62-year-old army officer commanding the 21st April Blackshirt Division. Drawn from a number of II Corps and Eritrean Corps formations, his large ad hoc battle group attacked Ras Immirù’s troops in the Seleclà region, at the Af Gagà Pass. High Command pinned a great deal of hope on this action.

Attempting to regain the strategic initiative in the face of an increasingly aggressive Ethiopian attitude, the Italian High Command called on Maggiore Generale Giacomo Appiotti, a 62-year-old army officer commanding the 21st April Blackshirt Division. Drawn from a number of II Corps and Eritrean Corps formations, his large ad hoc battle group attacked Ras Immirù’s troops in the Seleclà region, at the Af Gagà Pass. High Command pinned a great deal of hope on this action.

Conclusion

This huge battle lasted many hours. Only after nightfall did the Italians succeed in driving the Ethiopians from the Ad Gagà Pass. For two more nights Appiotti’s men repulsed several hard but mismanaged counterattacks, absorbing only a few additional losses. After ten days in the district the column departed and its troops rejoined their original corps. Despite the significant size of the forces engaged (12,000 Italians and 8,000 Ethiopians), this episode draws little attention in the Italian accounts of the campaign due to its strategically inconclusive result (the Ethiopians retained operational capability). Nevertheless, the operation succeeded in convincing Ras Immirù to renounce fighting the Eritrean forces in the Tucul sector. From now on, he only launched small hit-and-run actions in the Mareb, Axum, and Adowa areas.

Notes

This is a gigantic scenario: 114 Italian units against 74 Ethiopian ones, taking place on six maps. I think that makes it the largest scenario currently in print for Panzer Grenadier (we had a really huge one in the old Blue Division scenario pack). What makes this very different is the lack of artillery: no off-board artillery, and only three Italian on-board batteries. If you want to fight the enemy hordes, you’re going to have to do it up close and personal-like.

SCENARIO THIRTEEN

Graziani’s War: Olol Dinle Strikes Again

25 December 1935

During preparations for his impending offensive, General Graziani ordered his ally Sultan Olol Dinle to conduct a daring reconnaissance-in-force into the Uebi Scebeli area. The Italians reinforced Dinle with a machine gun platoon and a handful of Italian officers and NCOs (to coordinate radio and air support). Dinle’s 1,000 troops carried out political influence operations among clans and ethnic groups of the area, in addition to a number of scattered guerrilla operations. After several weeks of harassing actions, Dinle settled his troops into an old fort in Gabbà, about 350 km inside enemy territory. He had collected sufficient information about his opponent Degiac Beienè Merid and his imminent counterattack plans that he felt confident holding his position. Graziani had granted Dinle leeway to stand or retreat at his discretion. About 300 of Dinle’s men deserted rather than fight, but they were of low caste and he remained confident with his Sciaveli noblemen along with the promised Italian air support.

Conclusion

Olol Dinle’s tough Somali horsemen fought with exceptionally high morale, knowing that a slow, painful death faced any captured man, and repelled all the Ethiopian attacks during the night and the following day. On the morning of 26th, the daring Sultan and his men received aerial resupply from Italian aircraft dropping parachuted material with great precision into the fort. Meanwhile, other aircraft bombed and strafed the Ethiopians without mercy, disrupting their force. Eventually Degiac Beienè Merid, himself wounded, withdrew his forces with heavy losses. Olol Dinle’s depleted army marched toward the Italian lines having accomplished his mission of securing the Uebi Scebeli valley and weakening the left flank of Ras Destà deployment.

Notes

Fort Apache: The Ogaden. A band of Bande hold out against wave after wave of Ethiopian attackers, whose goal is to kill poor old Olol Dinde. Just because of decades of kidnapping, murder, cattle rustling and religion-inspired violence.

SCENARIO FOURTEEN

Graziani’s War: Raid at Areri

2 January 1936

Throughout November and December Ras Destà moved his well-equipped army in a slow advance toward the Somali border. Italian aerial reconnaissance noticed this mass and hammered it during their whole advance. This aeronautical grind disrupted and demoralized Ras Destà’s army by the first days of the new year despite the high morale shown at the beginning of the campaign. To support his imminent offensive, Graziani ordered another reconnaissance in force against areas under Destà’s control. This time the probe focused on the Areri region between Lake Huioi and the Ganale Doria Canal, 60 kilometers north of Dolo (Graziani’s main operating base). The Ethiopian garrison deployed there had not suffered as much as the rest of Ras Destà’s army, and repelled the first Dubat assault. The Dubats tried again the following day.

Throughout November and December Ras Destà moved his well-equipped army in a slow advance toward the Somali border. Italian aerial reconnaissance noticed this mass and hammered it during their whole advance. This aeronautical grind disrupted and demoralized Ras Destà’s army by the first days of the new year despite the high morale shown at the beginning of the campaign. To support his imminent offensive, Graziani ordered another reconnaissance in force against areas under Destà’s control. This time the probe focused on the Areri region between Lake Huioi and the Ganale Doria Canal, 60 kilometers north of Dolo (Graziani’s main operating base). The Ethiopian garrison deployed there had not suffered as much as the rest of Ras Destà’s army, and repelled the first Dubat assault. The Dubats tried again the following day.

Conclusion

Initially the Ethiopian troops defended their position staunchly, even launching daring attacks on both flanks of the approaching enemy force. The Lancia armored car unit become separated from the Dubats and suffered some mechanical failures. However, their brave crews always managed to repel the Ethiopians who tried to capture the stalled vehicles. Ethiopian casualties inexorably mounted, and when the freshly-arrived VII Arabo-Somali Battalion applied their pressure the Ethiopian’s morale broke. Their retreat left approximately 150 casualties on the field.

Notes

The Ethiopians are Imperial Regulars, and their firepower and morale advantages over the Bande are sizable; over the Colonial regulars, not so much. The Italians are on the attack, and both sides have hefty forces (though nothing like those of Scenario Twelve).

SCENARIO FIFTEEN

Graziani’s War: the Ganale Doria

13 January 1936

Ras Destà’s forces marched up the valley of the Ganale Doria River toward the waiting Italians. To soften up the advancing enemy, Graziani unleashed the 7th Bomber Wing of the Royal Italian Air Force. After decimating the Ethiopians with conventional bombs and two tons of mustard gas, on January 12th Graziani sent three columns forward. Bergonzoli and Morelli led their columns against Ras Destà’s main corps, while Agostini’s column marched toward Karavalis’ mercenary force. After a day of numerous minor engagements, Gen. Annibale Bergonzoli’s column met the enemy in his first major clash.

Conclusion

The Italians failed to drive out the Ethiopians the first day, and so the fighting continued the following day, and the next. Not until the 16th did Ras Destà’s men decide they’d had enough and abandon the field. At this point Bergonzoli had not yet grown the splendiferous beard that gave him his immortal nickname “Electric Whiskers.”

Notes

The Electric-Whiskers-to-be is leading a large force on a narrow front against a defending force of roughly equal size and morale, but less firepower. It’s tough to attack in Panzer Grenadier when both the numbers and morale are equal.

SCENARIO SIXTEEN

Graziani’s War: Martini’s Echelon

13 January 1936

A portion of Bergonzoli’s column, headed by Colonnello Martini, split off from the main force toward Ddei Ddei Wadi, aiming to deny the important wells at Bogol Magno to the enemy. Martini’s men collided with a sizable Ethiopian force and a spirited engagement commenced.

A portion of Bergonzoli’s column, headed by Colonnello Martini, split off from the main force toward Ddei Ddei Wadi, aiming to deny the important wells at Bogol Magno to the enemy. Martini’s men collided with a sizable Ethiopian force and a spirited engagement commenced.

Conclusion

Martini managed to defeat the brave enemy attack, but he failed to exploit his success. He halted his force a kilometer from the Ddei Ddei Wadi because a huge noise led him to think that enemy reinforcements were arriving. Actually, the Empress had sent a small fleet of trucks to rescue Ras Destà and his entourage, including the Belgian advisor Lieutenant Frère. The next day Martini received reinforcements and Bergonzoli assumed command. For the next two days, the general patiently and relentlessly cleared the wadi with the constant help of the Regia Aeronautica, who employed chemical weapons. These aerial attacks annihilated Ras Desta’s flocks of livestock (a source of both sustenance and prestige), demoralizing his huge force and forcing them to fight for every scrap of food and water. The ensuing engagements were pathetically one-sided, pitting Bergonzoli’s motorized columns against the starving, hiding Ethiopian troops. The bombastic fascist propaganda and Graziani’s postwar memoirs tried to paint this extermination as a series of “battles.” While Graziani’s use of chemical weapons is rightly condemned by most, his use of airpower to deliver “shock and awe” and his efficient use of logistics to keep his force supplied with fuel, food, and ammunition despite the austere environment are to be admired. On January 20th, Graziani’s victorious forces entered the town of Neghelli, from which Mussolini created a title of Marquis for the general. This propagandized success paled in reality to the difficulties experienced by Marshal Badoglio on the northern front.

Notes

This is a big scenario, with a large Italian force of Bande and colonial infantry try to smash their way through a huge Ethiopian force, one better-armed (more machine-gun platoons, and everyone starts at full strength) than usual. The Italians have tanks and armored cars and artillery; the Ethiopians have lots and lots of Ethiopians.

SCENARIO SEVENTEEN

First Tembien: Opening Clash

20 January 1936

During the first weeks of January, Ras Cassa, Ras Sejoum, Ras Mulughietà and Ras Immirù (fielding a force of over 150,000 regulars and irregulars between them) conceived a daring plan to destroy Marshal Badoglio’s forces near Adowa, followed up by an assault on Eritrean territory. However, across a front of least 200 kilometers, it was too ambitious a plan for four corps-sized masses with little radio communications, no air cover, and a significant level of rivalry among the Rases. Alerted by aerial reconnaissance and some minor engagements, Badoglio moved quickly and attacked the Ethiopians first. Thus began the First Battle of Tembien.

Conclusion

The Eritreans and Ethiopians fought a tenacious battle all day, and possession of the Mehenò village passed back and forth several times amid intense hand-to-hand fighting. By the mid-afternoon, however, the Italian-led troops had managed to clear the Zeban Kerkatà Hills of enemy forces, from which the obstinate but uncoordinated attacks had launched. This strong Ethiopian detachment failed its objective of infiltrating between two of the Italian corps, while another detachment in the same region was also identified and severely beaten by another Italian column. In fact, the other detachment was so damaged by preparatory artillery and machine-gun fire that rifle fire was not needed to break the force. To add insult to injury, Ras Cassa possessed one of the few radio sets in the field, and after this battle called the Emperor to admit his defeat, only to have the Italians intercept and listen in on the radio transmission. For the Italians, the First Tembien battle seemed an auspicious beginning.

Notes

This is a big scenario, and it’s going to be tough on the Italians: they’re on the attack and have superior firepower, but the Ethiopians seriously outnumber them and have slightly better morale. That’s going to make for some tough going.

SCENARIO EIGHTEEN

First Tembien: the Last Sweet Hours

21 January 1936

While the victorious Italians exploited their success at First Tembien by occupying Mount Lata, another Italian force marched from the opposite direction in an operational pincer maneuver. At dawn, as Tenente Colonnello Buttà’s Column resumed its advance, they met some tenacious but still uncoordinated resistance.

While the victorious Italians exploited their success at First Tembien by occupying Mount Lata, another Italian force marched from the opposite direction in an operational pincer maneuver. At dawn, as Tenente Colonnello Buttà’s Column resumed its advance, they met some tenacious but still uncoordinated resistance.

Conclusion

The brief battle caused very few losses to the Italians but many to the Ethiopians. While the Ethiopians launched numerous brave attacks, they never managed to overwhelm the Italians with their superior numbers. The one-sided fight quickly broke the will of Ras Cassa’s officers and their units fled the battleground. The MVSN units fought very well in the clash but scarcely mentioned the battle in their news reels. After sorting out the wounded, Tenente Colonnello Buttà continued their march toward the other arm of the pincer.

Notes

Large forces clash on a very small battlefield, with 53 Italian units attacking 60 Ethiopian ones. Italian morale is a little better and they have a (very) little artillery. Terrain favors the defending Ethiopians, so it’s going to be another hard fight for the Blackshirts and colonials.

SCENARIO NINETEEN

First Tembien: Legend of Uarieu Pass

22 January 1936

On the right of Marshal Badoglio’s army, a Blackshirt command operated from an old fort, employing “demonstrative actions” to keep Ras Sejum’s forces pinned to this area and unable to reinforce elsewhere. On the morning of the 22nd, Console Generale Diamanti led his column to briefly occupy Debra Ambà. En route Ras Sejum’s brave and well-equipped forces engaged the MVSN force in battle. Diamanti attempted to fight through the enemy but met growing resistance. He informed his superior, General Umberto Somma of the 2nd CCNN Division, about the danger of the massing enemy troops. Somma, residing inside Uarieu Pass fort, confirmed his orders to press on to Debra Ambà, and declared that, from his spotting position, the Ethiopians did not seem so many. As Diamanti arrived near Debra Ambà he realized that an enemy offensive was definitely in progress. Diamanti ordered a retreat to the fort but soon discovered that the Blackshirts were almost surrounded. Some artillery and machine guns exited the fort to help the retreating troops.

Conclusion

Pressed from two sides, Diamanti’s situation suddenly grew more complicated. Some locals passively watching the battle from the Uork Ambà perceived a likely victory for Ras Sejoum, and so grabbed their weapons and charged down the hill at the Italians, cutting the telephone line to the artillery at the fort in the process. The Diamanti column retreated through terrible hand-to-hand fighting, sacrificing the machine gun company and all the 65/17 batteries. The Ethiopians pursued the survivors to the fort, but another machine gun company and a 77mm battery exited the fort and stopped the Ethiopian horde’s advance long enough to get the survivors inside. Those guns were lost as well. The Ethiopians suffered significant casualties to their 3,000-man force, but bought a great victory with their dead. For their part, MVSN units lost 258 dead and 210 wounded, while the Eritreans lost 92 dead and 48 wounded. Both MVSN and Eritrean units suffered very high casualties among their officers. While a costly beginning of their offensive, Ethiopian hopes rose with the victory, and a short, hard siege soon began.

Notes

It’s the Black Day of the Blackshirts, as they face masses of Ethiopians determined to wipe them out. It’s going to be a tough fight among the hills and rocky ground, with the Blackshirts having to fight their way across a large map area with only a handful of reinforcements arriving to help out.

SCENARIO TWENTY

Endertà: Blackshirts and Black Feathers

12 February 1936

On February 11th, under very bad weather, Marshal Badoglio ordered his troops to resume the advance. He had prepared for the offensive by stockpiling a mountain of supplies, bringing up hundreds of trucks to haul them, and paving new roads for the new trucks. However, the weather turned many of the new roads to mires, forcing the troops to walk. Despite that, the first day of the advance went well. But on the second day, an MVSN division ran into troubles. In the early morning, just as the forces mustered for the day’s march, the 101st Blackshirt Legion came under fire by well-equipped and determined troops. Shortly thereafter, additional attacks from different sectors erupted as well.

On February 11th, under very bad weather, Marshal Badoglio ordered his troops to resume the advance. He had prepared for the offensive by stockpiling a mountain of supplies, bringing up hundreds of trucks to haul them, and paving new roads for the new trucks. However, the weather turned many of the new roads to mires, forcing the troops to walk. Despite that, the first day of the advance went well. But on the second day, an MVSN division ran into troubles. In the early morning, just as the forces mustered for the day’s march, the 101st Blackshirt Legion came under fire by well-equipped and determined troops. Shortly thereafter, additional attacks from different sectors erupted as well.

Conclusion

When the commander realized that the enemy was roughly handling his “green” Blackshirts (which included university conscripts), he ordered an elite Alpini battalion to their support. The Alpini overtook the Blackshirts and repulsed the Ethiopian attack. With the pressure reduced, the Blackshirts rallied, eventually making a joint attack and dislodging the enemy from their high ground defensive position. This first day of the Endertà battle claimed the most Italian lives of the multi-day action.

Notes

Finally, we get to use the ultra-cool new Alpini pieces (complete with the traditional black feather)! The Italian player is going to need them, and their climbing skills, as he or she faces not only large numbers of Ethiopian infantry, but the first appearance of Ethiopian heavy weapons.

SCENARIO TWENTY-ONE

Endertà: Dawn Fighting at Adi Sembet

13 February 1936

On the second day of the Endertà offensive, Marshal Badoglio intended to regroup the units that had pushed forward during the previous day. However, before dawn a brave Ethiopian attack developed against the well-drilled infantrymen of the Sabaudia Division. A battalion of the 46th Regiment easily repulsed the enemy’s initial rush, but in the second wave they faced a rude awakening.

Conclusion

The Ethiopians failed in this brief but bloody battle, and lost their brave and competent leader Bitouded Maconen Demissiè. During the fighting his death was kept secret to avoid a collapse of the Ethiopian morale. Later that day, reinforced by a few hundred cavalry, the Ethiopians sallied again only to be immediately checked by heavy Italian artillery support. Over the following two days the Italian advance proceeded without any serious obstacles as Ras Mulughietà’s forces were pummeled by heavy artillery and aerial bombardments, including again the widespread use of gas. A favored Italian tactic was to saturate key river fords and waterholes with Yperite, thereby hitting enemy concentrations and poisoning water sources. Furthermore, Italian intelligence had induced Galla tribesmen, traditionally hostile to the Ethiopian people, to launch harassing attacks on the retreating enemy. Ras Mulughietà’s son died from aircraft strafing during the chaotic retreat. Mulughietà, Imperial Minister of War, later tried to recover his son’s body personally, but the Galla captured and lynched him.

Notes

The Italians are dug in on the hills and awaiting the Ethiopian assault, which will likely come in two waves. There’s no artillery or sir support for either side, just hard close-quarters fighting by the poor bloody infantry.

SCENARIO TWENTY-TWO

Second Tembien: Uork Ambà

27 February 1936

On the morning Ras Mulughietà died seeking to recover his son’s body, Marshal Badoglio launched a small but important attack to support his campaign in the Tembien region. To start, he launched a commando-like strike using a small group of Blackshirts, Alpini, and Eritreans to conquer the pivotal Uork Ambà. This setback did not deter the Ethiopians, who over the next couple days fought perhaps the toughest action of the entire campaign against Generale Pirzio Biroli’s entire Eritrean Corps. The “commandos” on Uork Ambà faced this reality first when they raised the Italian tricolor after their own fine action.

On the morning Ras Mulughietà died seeking to recover his son’s body, Marshal Badoglio launched a small but important attack to support his campaign in the Tembien region. To start, he launched a commando-like strike using a small group of Blackshirts, Alpini, and Eritreans to conquer the pivotal Uork Ambà. This setback did not deter the Ethiopians, who over the next couple days fought perhaps the toughest action of the entire campaign against Generale Pirzio Biroli’s entire Eritrean Corps. The “commandos” on Uork Ambà faced this reality first when they raised the Italian tricolor after their own fine action.

Conclusion

Degiac Mesciescià Ilmà, a nephew of Emperor Haile Selassie, carried out repeated attacks. The bravery came to naught, however, as the resolute defenders held their ground. One Italian machine gun had been hauled up the Ambà escarpment with ropes, and laid down a withering fire. Although celebrated loudly by Fascist propaganda, this action actually held little relevance to the campaign and its outcome.

Notes

This is an unusual little scenario, with a handful of forces on each side. The Italians have superior morale, and while the Ethiopians will eventually have numbers they arrive in a slow drip of reinforcements, which will force the Ethiopian player to use infiltration tactics rather than gathering his troops for a mass human-wave assault.

SCENARIO TWENTY-THREE

Second Tembien: The Zebandas Clash

27 February 1936

Some of the most intense fighting of the entire campaign took place during the second battle of Tembien, on the lower flanks of the Uork Ambà near the town of Zebandas. The men following Degiac Bejenè may have claimed the title as the finest troops on the Ethiopian side in this war. Although not as thoroughly trained as the regular army, these men showed extreme motivation and an impressive ability to suffer hardship and still fight effectively. Console Ricciotti’s column on the northern slopes of the Ambà faced these giants among men.

Conclusion

The Blackshirts sustained at least ten furious counterattacks by of the forces of Meshashà Ilmà. All the Italian accounts of this clash report very heavy fighting in which the Ethiopians, even when out of ammunition or wounded, kept advancing armed with swords or even clubs. Only late in the afternoon did the exhausted Ethiopians, sensing that the Italians might surround and cut them off, begin withdrawing. Meshashà Ilmà, wounded in the battle, survived only by playing dead.

Notes

This is a big scenario, with a Blackshirt legion facing waves of very determined Ethiopian attackers. The Ethiopians have sky-high morale and fairly good numbers; the Blackshirts have average morale and a tiny dribble of off-board artillery (some very weak strengths here – but the Blackshirts are going to need them all the same).

SCENARIO TWENTY-FOUR

Second Tembien: The Wadi

27 February 1936

The right-hand Italian column moved from Uarieu Pass on an outflanking maneuver aimed to cut off the advancing Ethiopian formations. However, they soon encountered a dry wadi used by Ethiopians as an infiltration route in their attempts get into the rear of the Italian attack.

The right-hand Italian column moved from Uarieu Pass on an outflanking maneuver aimed to cut off the advancing Ethiopian formations. However, they soon encountered a dry wadi used by Ethiopians as an infiltration route in their attempts get into the rear of the Italian attack.

Conclusion

With only one path open to them, the Ethiopians had no choice but to press forward and so they did with unstoppable courage. After heavy fighting the Italians completely smashed Degiach Bejenè’s forces inside the wadi. Overwhelming Italian firepower killed most of the enemy combatants including Degiac Bejenè, his son, and many of his chieftains.

Notes

This is a big scenario, with lots of forces on both sides. The Ethiopians are trying to escape; the Italians are trying to stop them. The Ethiopians have better morale, while the Italians do have a little help from artillery.

SCENARIO TWENTY-FIVE

Second Tembien: South of the Mountain of Gold

27 February 1936

While a group of Blackshirts were engaged in sweeping Uork Ambà (translated as the Mountain of Gold), south of that height an Alpini battalion failed to surprise the enemy. When they realized they were in danger of being surrounded they sent for aid. Console Diamanti’s Blackshirt fire brigade was dispatched as reinforcements.

Conclusion

The Blackshirts managed to stop the outflanking attempt by the Ethiopians and, together with the Alpini, eventually pushed back and severely damaged the Ethiopian force defending the sector south of Uork Ambà. Over the next two days the second battle of Tembien became a scattered series of firefights most often decided by the preponderant Italian artillery or aerial bombardment. The Ethiopians performed less brilliantly than in the opening stage of the campaign, but the significant imbalance in forces (over 5:1 in the Italians’ favor) and massive edge in technology made this nearly a foregone conclusion. In his memoirs Marshal Badoglio wrote that the enemy had shown “the superb warrior ethos of the race” in this campaign. Resistance continued through the first week of March, requiring Badoglio to commit more troops to search and destroy duties.

Notes

It’s not enough for the Alpini and their Blackshirt friends to hold off the Ethiopians: they also have to push forward and take their objectives. That’s going to be tough even if the Blackshirt reinforcements arrive promptly.

SCENARIO TWENTY-SIX

The Scirè

29 February 1936

During this time period, General Pietro Maravigna had a reputation as a knowledgeable military historian and expert on doctrinal and strategic subjects. Marshal Badoglio entrusted Maravigna, appointed to command the Second Corps, with the task of enveloping Ras Imirrù’s army in the Scirè region of Ethiopia. The Marshal intended for this action take place within the framework of a larger maneuver he planned to isolate and annihilate the enemy. Exploiting one of the rare existing motor roads, Maravigna deployed his advancing troops in more of a “procession” than as an advancing army, without relying on scouting or on reconnaissance at all. He dispensed with such precautions because aerial reconnaissance signaled that the avenue of advance lacked potential threats. Being a skilled commander and well-advised by local clergymen, Ras Imirrù saw the opportunity to bloody the Italians’ noses. He ordered his most reliable forces to conceal themselves and await the advancing enemy.

During this time period, General Pietro Maravigna had a reputation as a knowledgeable military historian and expert on doctrinal and strategic subjects. Marshal Badoglio entrusted Maravigna, appointed to command the Second Corps, with the task of enveloping Ras Imirrù’s army in the Scirè region of Ethiopia. The Marshal intended for this action take place within the framework of a larger maneuver he planned to isolate and annihilate the enemy. Exploiting one of the rare existing motor roads, Maravigna deployed his advancing troops in more of a “procession” than as an advancing army, without relying on scouting or on reconnaissance at all. He dispensed with such precautions because aerial reconnaissance signaled that the avenue of advance lacked potential threats. Being a skilled commander and well-advised by local clergymen, Ras Imirrù saw the opportunity to bloody the Italians’ noses. He ordered his most reliable forces to conceal themselves and await the advancing enemy.

Conclusion

Ras Imirrù’s men ambushed the Gavinana Division’s vanguard, which quickly became disordered. Reinforcements from the division eventually drove off the Ethiopians after several hours of heavy fighting. Especially ironic, given Maravigna’s reliance on “modern” warfare, at one point the division was forced to form a 19th-century square with their artillery on the corners to cover all flanks against encirclement. As the battle surged the artillery often fired point blank into the mass of combatants, regardless of whether it contained friendly or enemy troops. The battle took Maravigna completely by surprise, who never realized Ras Imirrù planned this as a rearguard action to cover his withdrawal. In any case, he stopped his “fast” advance until the 2nd of March, drastically upsetting Badoglio and his plan. Thanks to the respite, Ras Imirrù, despite the heavy losses, escaped with a majority of his army. The rearguard launched further counterattacks which were checked by heavy artillery fire from the entire Second Corps. After the Second World War the two Italian generals, while writing their memories, accused each other of incompetence and poor leadership throughout the campaign. However, both agreed that Ras Imirrù possessed superior command qualities.

Notes

Ambush! An Italian column meanders peacefully across the board, with no flankers or scouts out to find any Ethiopians, and then all hell breaks loose.

SCENARIO TWENTY-SEVEN

Salt Spring

31 March 1936

The combatants fought the last major battle on the northern front at Mai Ceu. Under the direct command of the Emperor the most modern Ethiopian forces ever assembled, assisted by groups led by other Rases, would engage the Italians in this apocalyptic struggle. This last attempt of the Ethiopians to inflict a clear defeat on the Italians aimed at duplicating their overwhelming victory at Adowa in 1896. All of the Ethiopian leaders present were descended from victors at Adowa, and felt themselves to be living symbols of their ancient Christian empire. The sires at Adowa included Ras Makonnen (father of the Emperor), Ras Mangasha (father of Ras Sejum), Ras Mangasha Atikim (father of Ras Chebeddè), and as for Ras Cassa, he himself fought there as a 15-year-old alongside his father. Great expectations preceded this battle, from the aging veterans of Adowa to the best-trained new combatants (British- and Belgian-trained officers, former King’s African Rifles, and St. Cyr’s graduates like Keniats Chifli, who during the battle directed the only modern battery on the Ethiopian side). A throng of Priests, Bishops and even determined female fighters rounded out the group. Meanwhile, the Italians and their Askari allies, well aware of the Ethiopian concentration, waited in their defensive works for the impending attack.

Conclusion

This final Ethiopian army fielded significant numbers of artillery, anti-aircraft guns and, above all, officers educated in modern warfare by foreign military assistance missions. The famous Imperial Guard, Kebur Zabagnà, fought valiantly here for the Emperor. On the other hand, the Italians were fighting in improved positions, with a plethora of modern equipment, and intelligence assets that allowed them to know the Emperor’s intent in advance. The fierce Ethiopian warrior tradition would not be enough. Ethiopian morale ran high with the Emperor on the field. However, after a good initial rush that carried the outer works in some areas, stubborn defense by the Alpini eventually led a stalemate with heavy losses for the frontally-assaulting attackers. By early afternoon, reinforcing Eritrean battalions allowed the Italians to push back the attacking forces. Late in the afternoon the Negus attempted several other costly attacks but the redoubtable Italians and their Askari allies again repulsed them. At the end of the day the Emperor ordered the withdrawal of his spent army, leaving a few small contingents to cover the retreat. From now until the conquest of Addis Ababa, Marshal Badoglio faced no more battles.

Notes

A big scenario with big forces deployed, including a full 32 (thirty-two!) platoons of the Ethiopian Imperial Guard. The Ethiopians have huge numbers, very high morale, superior initiative, some actual support weapons and more off-board artillery than the Italians bring to bear. This one is going to be hard on the defender, despite his own strong numbers.

SCENARIO TWENTY-EIGHT

Second Ogaden: Battle of Gianagobò

15 April 1936

Marshal Badoglio’s successes on the northern front frustrated the vain and envious General Rodolfo Graziani in the south. Hampered by terrible rains and a lack of roads, Graziani delayed repeatedly as he built up his infrastructure and supplies. Mussolini, ignorant or just uncaring of the difficulties, repeatedly urged the general to resume the offensive in the southern sector. Against his better judgment, Graziani finally ordered several mobile columns to further penetrate into Ethiopian territory. The left column headed for the strategic Korrak Wadi near Gianagobò, but encountered a surprise.

Marshal Badoglio’s successes on the northern front frustrated the vain and envious General Rodolfo Graziani in the south. Hampered by terrible rains and a lack of roads, Graziani delayed repeatedly as he built up his infrastructure and supplies. Mussolini, ignorant or just uncaring of the difficulties, repeatedly urged the general to resume the offensive in the southern sector. Against his better judgment, Graziani finally ordered several mobile columns to further penetrate into Ethiopian territory. The left column headed for the strategic Korrak Wadi near Gianagobò, but encountered a surprise.

Conclusion

Olal Dinle’s tough Somali Dubats met stiff resistance as they closed on the wadi. Gen. Guglielmo Nasi soon dispatched Libyan troops to reinforce their efforts and some of them, with the support of tanks, reached the wadi. However, due to recent heavy rain the wadi was in flood and posed a major obstacle. To make things worse the Ethiopians had skillfully exploited the caves and broken terrain on the opposite side of the wadi. Some Ethiopians attempted to infiltrate the Italian positions but were repelled with the aid of the tanks. The first day of the battle ended in a bloody stalemate. Only a small Italian detachment managed to cross the wadi (and that was in a marginal sector not portrayed in this scenario). However, Gen. Franco Navarra’s forces reestablished contact with the left side of the Nasi’s column. Nasi, one of the best officers of Regio Esercito during both the Ethiopian and Second World Wars, methodically prepared for the rest of the day and night for the following day’s battle in which his troops outflanked the Ethiopians, who quickly gave ground.

Notes

The Ethiopians have numbers on their side, and they have caves. The Italians and Somalis are on the attack with lesser numbers and morale slightly inferior to that of the defenders – it’s going to be tough for Il Duce’s men to succeed.

SCENARIO TWENTY-NINE

Second Ogaden: Battle of Bircut

19 April 1936

After the Gianagobò battle the Nasi column limped to the water wells of Bircut. Nasi deployed the trucks of his fast column and two regiments of Libyan troops at the center of a large valley. At dawn, an Ethiopian caravan composed of thirsty troops that had withdrawn from Gianabobo tried to storm past the Italians to reach the wells. Their surprise assault, if successful, would refresh the Ethiopians and enable a disciplined retreat to continue.

Conclusion

Nasi’s men fought well against the surprise attack by the thirst-crazed Ethiopians, but could not hold them off. The Ethiopians claimed the wells by mid-day and the Italians drew off to regroup. The following morning, with the help of concentrated artillery and airpower, Nasi’s men drove off the battered Ethiopians for good. This was the last major battle of the war. On May 5th the Italians entered Addis Ababa; this officially ended the conflict but it was far from the end of the story.

Notes

Here we have another big scenario, with masses of Ethiopians trying to wipe out the Italian force that starts on the board before reinforcements can arrive to save the day. It’s yet another battle in which the heaviest weapons by far are the Italian 65mm mountain artillery batteries: infantry rule this battlefield.

SCENARIO THIRTY

Ras Destà Strikes Again

19 May 1936

Soon after the ceasefire, Marshal Badoglio turned over control of Ethiopia to General Graziani, the new Viceroy. Graziani’s first task was to pacify the newly-declared Italo-Ethiopian Empire that still simmered with discontent. Two small but well-armed armies, each counting 15,000 men, still held out in the hinterlands. To make matters worse, perhaps as many 20-30,000 soldiers from the Negus’ defeated armies had returned to their native regions and formed bandit gangs. The regions of Galla, Borana and Bale were particularly turbulent. In those areas, Italian forces engaged in several minor but costly clashes before a major incident occurred. A large group of Ethiopians closed in on the town of Neghelli, where Graziani claimed his new heraldic title (Marquis of Neghelli). The Regia Aeronautica bombed the rebels for two days using large amounts of mustard and phosgene bombs in addition to conventional explosives. At that point the impetuous General Annibale Bergonzoli felt confident enough to attack the enemy.

Soon after the ceasefire, Marshal Badoglio turned over control of Ethiopia to General Graziani, the new Viceroy. Graziani’s first task was to pacify the newly-declared Italo-Ethiopian Empire that still simmered with discontent. Two small but well-armed armies, each counting 15,000 men, still held out in the hinterlands. To make matters worse, perhaps as many 20-30,000 soldiers from the Negus’ defeated armies had returned to their native regions and formed bandit gangs. The regions of Galla, Borana and Bale were particularly turbulent. In those areas, Italian forces engaged in several minor but costly clashes before a major incident occurred. A large group of Ethiopians closed in on the town of Neghelli, where Graziani claimed his new heraldic title (Marquis of Neghelli). The Regia Aeronautica bombed the rebels for two days using large amounts of mustard and phosgene bombs in addition to conventional explosives. At that point the impetuous General Annibale Bergonzoli felt confident enough to attack the enemy.

Conclusion

The Italian force, composed of two battalions, advanced into a wooded area. The leading battalion was ambushed and suffered heavy losses. The other battalion could not provide help as it was blocked by Ethiopians as well. The first battalion fought hard to disentangle itself and eventually rejoined the second battalion. For the first time the Italians faced Ethiopia’s most successful guerrilla chief, Dejazmach Gabre Mariam, and Ras Destà had entrusted him with the command of the most disciplined troops available. Snatching up a rifle, Bergonzoli fought in the front rank and was seriously injured when an Ethiopian bullet struck his weapon’s breech. “You’ve destroyed the best rifle I ever had in my life!” the bleeding Bergonzoli shouted at the Ethiopians, but he confirmed his foes’ bravery in his memoirs. Evacuated over his strenuous objections, Bergonzoli would grow his famous “Electric Whiskers” while recovering from his wounds.

Notes

You simply can’t have enough scenarios featuring Electric Whiskers.

SCENARIO THIRTY-ONE

Addis Ababa – Djibouti Railway I

5 July 1936

Immediately following his conquest of Addis Ababa, Marshal Badoglio resigned his post and returned to Italy. Mussolini awarded the Viceroy position to Graziani, and promoted him Marshal of Italy. The new Viceroy faced acute internal disorder within his area of responsibility. But expectations at home ran high that he would check the rebels, given his former success in crushing the Libyan guerrillas during the 1920s. One of his initial priorities involved securing the Addis Ababa – Djibouti railway which brought in significant supplies and trade goods, and suffered frequent guerrilla attacks allegedly supported from the French colony at Djibouti. A series of clashes along this line started with the derailing of a train beside the Zalalacà outpost. The new government made several attempts to free the besieged troops in the following two days.

Conclusion

Several hours after the fighting began, a small Italian relief force departed by train from the village of Lasabbas. However, the Ethiopians derailed the train very close to the besieged detachment, forcing the relief force to join the outpost’s defenders. The Ethiopians had no explosives or hand grenades, but piled debris on the tracks to force the derailment. During the night another small platoon tried to help the besieged by departing from Lasabbas on foot. Unfortunately for them, the Ethiopians intercepted and encircled them, forcing the Blackshirts to entrench inside a wadi. The Italians very much feared being taken prisoner by Ethiopian rebels and fought to the death. Only two Blackshirts managed to escape. The following day Console Galbiati, the commander of the 219th Legion, arrived with a motorized company to relieve the beleaguered garrison. Although injured in the skirmishing, Galbiati managed to repress the local rebellion but uncoordinated disturbances continued through the 17th.

Notes

Developer John Stafford loves this sort of weird scenario, with a couple of Italian trains tootling around (well, one’s tootled its last but the other can move) and the Ethiopians trying to hold up the train and wipe out the Blackshirts.

SCENARIO THIRTY-TWO

Addis Ababa – Djibouti Railway II

7 July 1936

The day following the first attack on the Zalalacà garrison, Console Galbiati, commander of the 219th Legion, led a motorized company into Las Addas station, but suffered a wound in the process. The Ethiopians contested the approach and almost encircled the village. Galbiati spent the remainder of the day fortifying the Italian positions and recalling an HMG section from a far hill position. His preparations paid dividends as the Las Addas garrison faced further attacks during the ensuing night. None of the attacks succeeded nor did those carried out against the isolated detachment in Zalalacà. The solution for the stalemate was, however, very close at hand.

The day following the first attack on the Zalalacà garrison, Console Galbiati, commander of the 219th Legion, led a motorized company into Las Addas station, but suffered a wound in the process. The Ethiopians contested the approach and almost encircled the village. Galbiati spent the remainder of the day fortifying the Italian positions and recalling an HMG section from a far hill position. His preparations paid dividends as the Las Addas garrison faced further attacks during the ensuing night. None of the attacks succeeded nor did those carried out against the isolated detachment in Zalalacà. The solution for the stalemate was, however, very close at hand.

Conclusion

Although driven off, Dejazmach Ficrè Mariam’s attack showed the increasing threat the guerrillas posed in the vicinity of Addis Ababa. The Italians shrugged off their losses and repaired the damaged railway. But Graziani, considered a leading expert in counterinsurgency at the time, knew how precarious the situation remained and ordered clearing operations along the railway.

Notes

Another train scenario, this time with a relieving force coming to save the Blackshirts but a very large group of Ethiopians ready to stop them.

SCENARIO THIRTY-THREE

Addis Ababa – Djibouti Railway III

8 July 1936

Despite losing his first engagement in the area, Dejazmach Ficrè Mariam did not feel himself beaten. After gathering new men and arms from the nearby villages he encircled the important Moggio Presidium, the base of Italian operations in the area. This time, however, he faced prepared men and defenses.

Conclusion

The Italians drove off Mariam’s attack while the Ethiopians suffered heavy losses due to the Italian readiness and disciplined fire. The siege, however, continued with small actions until the evening of the following day when the entire 1st Eritrean Brigade commanded by General Vittorio Gallina arrived from Addis Ababa. Ficrè Mariam recalled his forces in the face of this overwhelming superiority, and the Eritrean brigade initiated brutal reprisals against the local population who had succored Ficrè Mariam with support and local levies.

Notes

Mussolini knew better than to declare the end of major combat operations before they were actually over: Ethiopia may have been defeated, but no one’s bothered to tell the Ethiopians. A large Ethiopian force is trying to overrun a Blackshirt fort, with no reinforcements in sight.

SCENARIO THIRTY-FOUR

Addis Ababa – Djibouti Railway IV

8 July 1936

Despite the Italian occupation of all the Empire’s cities and defeat of her armies, Ethiopia never formally surrendered and those troops still in the field continued to fight. While the Italians dealt with the insurgency at Moggio, another train transporting troops from Dire Dawa to Moggio encountered more Ethiopian rebels not far from Adama, a large settlement 100 kilometers from Addis Ababa. Heavy fighting ensured.

Despite the Italian occupation of all the Empire’s cities and defeat of her armies, Ethiopia never formally surrendered and those troops still in the field continued to fight. While the Italians dealt with the insurgency at Moggio, another train transporting troops from Dire Dawa to Moggio encountered more Ethiopian rebels not far from Adama, a large settlement 100 kilometers from Addis Ababa. Heavy fighting ensured.

Conclusion

Although the Italians were able to repulse the attack on their train, the Ethiopians forced them to head back to Adama. None of these harassments succeeded in interrupting the railway for long, but they highlighted that their victory over the Negus did not mean that Italians controlled the country.

Notes

Once again we’ve got a train loaded with Blackshirts, and this time they have a tank with them (also loaded on the train – it’s a very small tank). The Ethiopians have blocked the railroad at some unknown spot, and it’s up to the blackshirts to bop their way past.

SCENARIO THIRTY-FIVE

Assault on Addis Ababa

28 July 1936

Several rebel groups launched uncoordinated attacks toward the outlying villages surrounding Addis Ababa. They hoped to raise the civilian population against the occupying Italian forces and their deeply-hated Eritrean Askaris. On the western side of the city one of the main rebel groups tried to move directly on Graziani’s headquarters. The sheer size of the main body inhibited a successful infiltration among the Italian strongholds without being detected. But some of the force made it in.

Conclusion

The Ethiopian attempt failed badly. The huge battle group found itself stymied by the tiny Air Force Headquarters Garrison. Then, reinforcements arrived on their flanks changing an attack into a rout followed by mopping up actions by the colonial Banda. In the following days the Ethiopian resistance carried out additional unsuccessful attempts, with some being nearly annihilated. Eventually one of the main instigators fell into Italian hands, a very influential clergyman named Abuna Petrus. He received a pro forma trial and a summary execution shortly thereafter. At the firing squad he blessed both the judge and his executioners while vindicating his role in the patriotic resistance.

Notes

A truly massive force of low-morale Ethiopians attempts to overcome a small Italian Air Force garrison (with sky-high morale!) before reinforcements can come and save them. The Italians get to use not only the Air Force troops, but Carabinieri too.

SCENARIO THIRTY-SIX

Addis Ababa – Djibouti Railway V

12 October 1936

After the July Addis Ababa debacles the railway to Djibouti operated unmolested for a while. The Italians only controlled a narrow corridor along the railway line, and slowly the rebels regrouped elsewhere in the following months. The Regia Aeronautica bombed suspected rebel camps as they were discovered, often using chemical munitions. On the 10th of October Ficrè Mariam reappeared attacking three irregular bands serving under the Italian flag. Two days later a major strike was attempted by one of his subordinates. The rebels targeted a special train transporting the Minister of the Colonial Empire Alessandro Lessona. Italian aviation helped check this attack and others. Eventually Viceroy Graziani mounted a complex operation directly against Ficrè Mariam’s sanctuary around Mount Boccan.

After the July Addis Ababa debacles the railway to Djibouti operated unmolested for a while. The Italians only controlled a narrow corridor along the railway line, and slowly the rebels regrouped elsewhere in the following months. The Regia Aeronautica bombed suspected rebel camps as they were discovered, often using chemical munitions. On the 10th of October Ficrè Mariam reappeared attacking three irregular bands serving under the Italian flag. Two days later a major strike was attempted by one of his subordinates. The rebels targeted a special train transporting the Minister of the Colonial Empire Alessandro Lessona. Italian aviation helped check this attack and others. Eventually Viceroy Graziani mounted a complex operation directly against Ficrè Mariam’s sanctuary around Mount Boccan.

Conclusion

Ficrè Mariam and his most important subalterns died together at the end of this engagement. Counted among those followers was a businessman from Addis Ababa who had helped him by providing the tools used to sabotage the railway line. The Eritreans burned villages and killed livestock to punish and disrupt popular support for the guerrillas, complying with Graziani’s methodology which he’d refined against Libyan rebels in the 1920s. The suppression campaign disorganized the Ethiopian resistance in the areas surrounding the railway, though small engagements still occurred. By the end of that year resistance began to subside.

Notes

No trains this time, just a small Italian garrison beset by a far larger force of Ethiopian attackers, with waves of Italian reinforcements plus some more Ethiopians steadily arriving to make the battle larger and larger.

SCENARIO THIRTY-SEVEN

Focus on Ras Destà

20 October 1936

Ras Destà’s army was one of the few still active after the Negus’ escape. The force counted six thousand warriors equipped with machine guns, 20mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns, and Rheinmetal anti-tank guns. To counter it, Graziani formed the “special division”, largely motorized and well equipped with artillery, armored cars and light tanks. However, its commander, General Carlo Geloso, faced a tough opponent on his own turf in the Sidamu region.

Ras Destà’s army was one of the few still active after the Negus’ escape. The force counted six thousand warriors equipped with machine guns, 20mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns, and Rheinmetal anti-tank guns. To counter it, Graziani formed the “special division”, largely motorized and well equipped with artillery, armored cars and light tanks. However, its commander, General Carlo Geloso, faced a tough opponent on his own turf in the Sidamu region.

Conclusion

Dejazmach Gabre Mariam fought bravely, manning an anti-tank gun himself for hours. However, at the end of the day the accumulated heavy losses and constant Italian pressure force him to retreat. The Italians lost the entire armored company but captured their assigned ground. Additionally, the sudden retreat of the Ethiopians allowed them to capture enough German-made anti-tank guns to establish an anti-tank battery (later used against the British in 1941).

Notes