(From notes compiled in the January-February edition of the US Army Artillery Journal on the use of Artillery in Ethiopia).

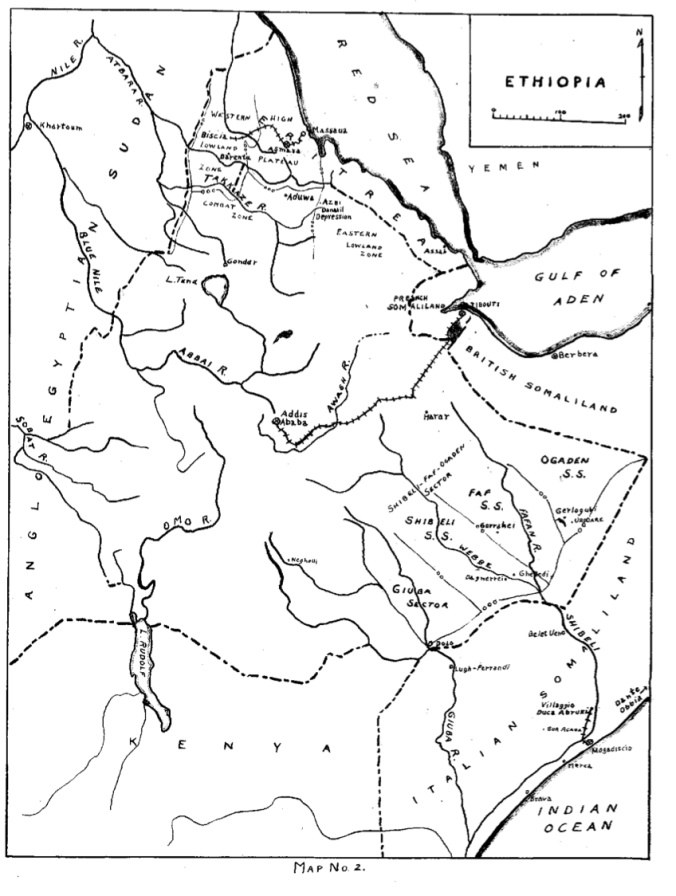

As time goes on the magnitude of the Italian effort in Ethiopia becomes more apparent. An idea of the difficulties encountered and of the efforts required to overcome them may be gained by a study of artillery employment on the Eritrea and Somalia fronts. These fronts will be considered in turn, for they present marked differences in terrain, forces involved, and tactics employed.

.

ERITREA EXPEDITION

TERRAIN

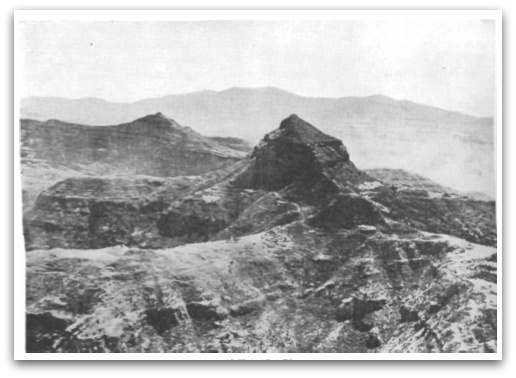

The terrain confronting the northern Italian columns consisted of a high plateau extending parallel to the coast at a mean height of 2,000 meters and cut by deep and rugged valleys. The few roads and trails followed the main ridge along the center. They were wide enough for fairly easy going along the levels but became only mule or foot paths in the valleys. The principal one, the so-called imperial highway, was no more than a mediocre dirt road with no maintenance.

Nevertheless, in dry weather on the flats, travel was generally simple, even formotorvehicles,owingtotheeaseof moving across country and of improvising trails. In the valleys and on the slopes, however, movement was almost always difficult and required special measures or the construction of roads.

Both truck and tractor columns were able to move and maneuver closely in rear of the troops, particularly when furnished with the assistance of an escort of foot troops, as was normal. Pack artillery was always able to move where needed and even the truck units nearly always found some way to advance. Observation was excellent from the many high points and isolated hills overlooking the plain, air observation rarely being needed. There was no lack of both surface and ground water. The latter is found at shallow depth, sometimes even constituting an obstacle to motor movement.

From an artillery standpoint, the generally favorable conditions of maneuver, the absence of natural limitations to fire, and the excellent possibilities for observation and signalling favored a large-scale employment of every type of field piece, except the heaviest calibers. Naturally, the exceptional conditions and the grave difficulties of supply required special measures in the organization of troops and trains and in manner of their employment

ORGANIZATION.

The artillery plans and preparations for the expedition were based on the foregoing considerations, the need for light, fast units, and the absence of enemy artillery. A reorganization of units included motorization to the greatest possible degree with a considerable reduction of battery personnel and materiel. The number of guns was cut down to conform to the possibilities of ammunition supply; the trains of pack batteries were motorized; truck-drawn batteries were reduced to three pieces; and the reserve artillery was given the fastest trucks available.

The peacetime artillery of three native batteries (65/17 guns*) and three companies of foot artillery for manning the frontier forts was finally augmented and so organized as to provide:

- Four native pack mule battalions of three batteries (65/17 or 75/13), one for each native brigade.

- Three native tractor and truck battalions of three batteries (77/28).

- Two truck-drawn battalions of three batteries (105/28) manned by Italian nationals.

- Four native fortress artillery groups of twenty-four batteries, together with a like number of national groups. These groups disposed of 400 pieces of various calibers (120, 105, 77, 75, 76) intended for the forts in being and those to be constructed.

From Italy were received the motorized battalions of the general reserve artillery and the organic artillery of the divisions constituting the expeditionary force, together with the necessary cadres to complete the colonial units.

In order to provide a solid defensive organization for the colony, three lines of fortified posts were constructed along 300 kilometers of front on the southwest frontier. These were capable of all-around defense, and were provided with fifteen to thirty days’ supply of ammunition, food, and water. They were manned chiefly by artillery (82 batteries of 320 pieces) and a truck transport pool was created to facilitate the movement and reinforcement of these units. This system of posts was pushed forward during the advance into Ethiopia to provide protection for the occupied areas—an extremely difficult and laborious task.

As an experiment, two especially mobile motorized battalions of 77/28 were organized for close-support missions in any terrain. The guns were knocked down into suitable loads and transported on light trucks, supplemented by small mountain tractors and trailers for supply and for movement in and around

the battery positions. The battalion combat and field trains were truck units. Owing to the impossibility of securing all the required motor equipment, the utility of these motor pack units could not be fully determined.

A groupment of battalions (100/17 and 149/13), motorized, arrived from Italy to constitute the general reserve artillery.

(*The usual Italian system of describing artillery. In general, the top figure represents the caliber in millimeters and the lower figure the length in calibers).

TRAINING.

By means of schools, tactical exercises, and firing practice, the whole expeditionary artillery was rapidly made familiar with the following principles of employment:

a. The necessity and possibility of pushing immediately in rear of the infantry ready for prompt action in order to utilize the artillery superiority to the utmost degree. Hence: Careful selection and reconnaissance of routes; provision of special means to overcome terrain difficulties; assignment of engineer and infantry detachments as escorts to facilitate artillery movement.

b. Fire action in close support of the infantry. Hence: Liaison detachments with each infantry battalion at least; observation well forward; sure means of target identification and preparation of fire (charts and maps); simple but sure communication (maximum use of visual signalling).

c. Decentralization of command and of firing units, but with the possibility of centralization by even the highest commander when necessary. Hence: Each battalion in direct support of a designated infantry unit with priority of fire missions in its zone of action, but in communication with the higher artillery commander for other missions: continuous forward reconnaissance by both battery and higher commanders, to insure prompt displacement behind the advancing infantry.

Owing to the special conditions of terrain and the enemy weakness in artillery and air forces, battery positions were selected further forward near their observation posts, and were closely grouped to simplify the organization of command, communication, and fire. In these forward areas each battalion and isolated battery had to provide strong all-around machine-gun defense of its positions.

Air observation was planned and provided but was not much employed in the actual operations. It was rarely needed, except for the indication of targets and a limited amount of surveillance.

The corps topographic sections and the army map section, together with a colonial topographic section organized prior to their arrival, were practiced in rapid preparation and distribution of charts and maps. The work of these sections, in conjunction with the airphoto sections, was particularly effective and valuable during the entire advance.

OPERATIONS

First phase.

The information of the enemy at the beginning of active conflict in October gave no indication for any particular apportionment of the reserve artillery. It was finally assigned to columns according to the roads available.

Hardly a round was fired during the initial advance, which was made in three columns:

- The west column (2d Corps) to Adua (Adowa);

- The center column (Eritrean Corps) to Enticcio;

- The east column (1st Corps) to Adigrat.

The difficult marches, however, furnished a large-scale test of the maneuverability of the new artillery units, both pack and truck. The truck-drawn units were able to follow closely, except those of the center column, which were held up by

impassable mountain terrain about thirty kilometers north of Enticcio. Had infantry and engineer detachments been furnished during this period it is certain that no delay would have occurred in the artillery advance. The light trucks and the tractors, particularly, demonstrated exceptional maneuvering power over difficult ground.

As soon as the first objectives were attained, the fortress artillery was brought forward to man the second and third defensive lines of the newly occupied territory. Within a few days twenty batteries had arrived as a nucleus of this defense.

Second phase.

The long advance to the Macalle- Tembien-Tacazze line, over increasingly difficult and little-known country, gave additional evidence of the maneuverability of the truck-drawn artillery. The native battalions of 77/28 and 105/28 followed immediately behind the infantry and were soon joined by the battalions of 149/13.

As before, the defensive batteries were moved forward promptly, fifteen of them being used along the line of communications in the Macalle sector alone.

Third phase.

After the relief of General di Bono and the assumption of command by Marshal Badoglio, the operations took on a new character and a new tempo. The enemy had concentrated two strong forces, one under Ras Mulugueta south of Amba Aradam, the other under Ras Cassa south of Tembien.

In this situation, almost all of the truck-drawn artillery was concentrated in the vicinity of Macalle as a general reserve under the army commander. Two groupments, a total of eleven battalions and thirty-four batteries, were formed. Some of these were brought forward by forced marches of 500 kilometers in four or five days, over the few trails, or across country under extremely difficult conditions.

The artillery action in the ensuing battle of Enderta in February was intense, continuous, and often decisive. In the double envelopment of the strong and extensive Amba Aradam position, the gap betwen the two corps was particularly dangerous. Two or three battalions of the motorized reserve artillery were attached to each corps for protection of the outer flanks, the remaining five battalions being disposed centrally in front of Amba so as to cover the front of both corps and with neutralization and interdiction missions along the entire strong enemy front together with the particular mission of protecting the corps’ inner flanks.

Battalions were massed close to their observation posts and the infantry lines, prepared for close defense, and joined by a very complete communication net to infantry and higher artillery commanders. A gridded map, 1/50,000, was widely distributed to both infantry and artillery for location of targets and preparation of fire.

The fire throughout was prompt, sure, and effective. After a rapid but intense preparation by all the artillery, the infantry began its long advance, constantly supported and protected by the batteries, which were particularly active in breaking up counterattacks. Frequent displacements were required, many of them of six or seven kilometers. In the five days of this battle which routed the Ethiopian forces, the artillery fired 26,000 rounds, half being expended by the reserve artillery.

About half of the reserve artillery was now sent to Scire and Tembien for action against the remaining enemy forces. The movements were made by forced marches and with great rapidity. One battalion of 149/13 moved 550 kilometers in three days over practically trackless country.

Fourth phase.

In the latter part of March, the Ethiopians were reported concentrating their best troops around Ascianghi for a last stand. These forces were believed to possess artillery in considerable amounts which were later found to be much exaggerated. For this reason, every effort was bent toward providing for the advance of particularly mobile units of reserve artillery to supplement the organic division pack artillery whose effectiveness was now much reduced by the loss of a disturbingly large number of its animals.

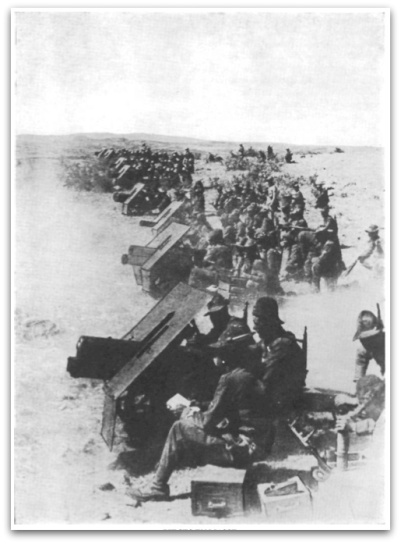

ITALIAN NATIVE TROOPS IN ETHIOPIA WITH 65-mm. ACCOMPANYING GUN

The zone of advance was more difficult than any yet encountered. On one stretch of 50 kilometers there were three mountain passes at least 3,000 meters high traversed only by mule or foot paths. All available troops, including the greater part of the artillery personnel, were set at work constructing a road. Fifteen days were allowed for its completion but the task was abandoned as too long after a week or so of labor.

The approach of the rainy season and the increasing enemy activity called for a speedy advance. A route was selected over which the artillery was to be dragged or carried. A groupment of reduced battalions of six to nine pieces, according to the number of light trucks available, was formed. Pieces were disassembled into transportable loads. The whole effort of this groupment was directed toward moving the guns of four battalions.

Another groupment was formed by the personnel of the other five battalions of the reserve artillery with the mission of assisting the movement of the guns and carrying out the necessary reconnaissance and preparations for their immediate employment in the new zone. In spite of the rains, by the end of March, a week ahead of the time expected, two battalions of 100/13 were in position, and rendered invaluable assistance in breaking up the enemy attack which began on April 1st. Similarly, in the subsequent advance on Addis Ababa, the artillery was present, ready to support the infantry on every occasion.

****

The northern operations presented many features of special interest to the artilleryman. Particularly noteworthy were the maneuverability of truck-drawn units, the appearance of motorized pack artillery, the utilization of fortress artillery to protect the zone of communications, the determination to keep the guns in immediate touch with the infantry in all situations, and the insistence on having a highly mobile artillery mass of maneuver in hand under the immediate control of the commander-in-chief.

.

.

SOMALIA EXPEDITION

TERRAIN.

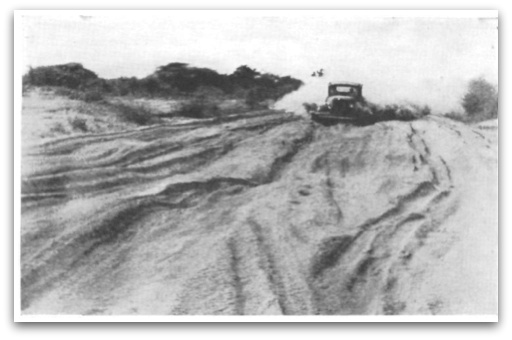

The lower Somala plain extends from the coast for hundreds of miles into Ethiopia, wooded and flat, covered with thorny bush—a “spiny fog of green” during the wet season; parched, dusty, and yellow during the dry months. Traversed only by native trails and by a few sluggish streams, this vast territory offers a formidable obstacle to any advance.

In such a country, the impossibility of local supply, even of water, necessitated long lines of communications and strict subordination of operations to the maintenance of these lines. Tactically, the limited possibilities of orientation, communication, observation, and maneuver, together with the necessity for constant security measures on all sides, constituted a peculiarly difficult problem.

On the higher plateau, four or five hundred miles inland, the terrain becomes similar to that of the great central highland described in the account of the northern operations. Rather open in character, broken by rugged hills and deep valleys, with few roads or trails, it presented only the usual difficulties encountered in mountain country.

TRANSPORT.

The few dirt trails existing at the beginning of hostilities were soon churned up into clouds of dust in dry weather, and seas of mud in the wet season, by the constant stream of trucks floundering along them. Nevertheless, both troops and supplies were brought up, in spite of the fact that four or five hours were often required to move a single kilometer ahead. Naturally, the roads were improved as time went on, but it must be remembered that the distances were great and road material extremely limited. The distances from the port of Mogadiscio to the various advanced bases were from 300 to 1,000 kilometers.

Truck transport was used from the coast to the combat zone, camels and pack mules from there forward. Of these, the mule was considered superior.

TROOPS.

Prior to the border incident at Ual Ual in 1934 the troops in Somalia consisted of a few Arab-Somali battalions and camel pack batteries, one company of tanks with a section of armored cars, together with air, engineer, and service detachments. Prompt measures were taken to build up an effective establishment and by the end of March, 1935, the Somali Expeditionary Force, comprising both Italian and native contingents, under General Graziani, was formed and ready.

Of the native troops, the Arabs made the best soldiers, although the Somalis were excellent. The latter were particularly tireless and rapid marchers, moving regularly 20 to 25 miles a day without fatigue.

The native divisions were organized in the same manner as those of the metropolitan force (3 infantry regiments of 9 battalions, 1 artillery regiment of 3 or 4 battalions). The artillery (65/17 and 77/28) was packed by camels. Combat and field trains employed both camel and mules as pack animals.

ENEMY.

The enemy was known to have large forces, under the command of Wehib Pasha, a Turkish soldier of fortune in Ethiopian employ. The Abyssinians possessed good rifles, many machine guns, a few armored cars, and some artillery. The artillery comprised mostly pieces of small caliber (37-67 mm.) of various models, with many kinds of ammunition, good, bad, and mediocre. A considerable number of modern weapons like the Oerlikon gun were on hand, together with ancient types such as the model 1861 iron cannon (120-150 mm.) using black powder. There were eighty-nine of the latter, purchased as a great bargain from a European power in 1914.

In the wooded lower plain, the enemy employed small mobile bands, moving rapidly, striking quickly from any direction, and disappearing promptly into the jungle. These bands were sometimes detached from larger units organized for defense in holes, caves, and scattered trenches, with riflemen and machine guns well concealed under trees and bushes.

On the high ground, the enemy resistance became more compact and his defenses and troops more readily located by ground and air observation. The town of Gorrahei, for example, one of the main objectives was an organized locality, covered by a double system of trenches, and armed with machine guns, trench mortars, and artillery.

COMBAT.

From the start the advancing columns were compelled to move slowly with reduced distances, reconnaissance pushed far forward, and with strong security detachments on all sides. The long approach marches, with all elements ready for action in any direction, were characterizedbysuddencontact,followed by rapid and close combat against an aggressive and mobile enemy who might appear anywhere at any moment. Surprise was the dominating factor; carelessness was unpardonable.

Under such conditions, sudden and rapid fire action was required from the supporting artillery. With little or no time available for coordinated plans of fire, with the difficulty of identifying and designating targets, and with very limited means of communication, the infantry had to rely mainly on its own weapons. The employment of the 65/17 as accompanying artillery in the infantry front lines was indicated and attempted. However, as this was a camel pack weapon, it was hardly adapted to such a mission. Trucks were improvised to haul a few pieces; but, in general, it was considered better to keep the batteries together out of immediate contact with the infantry, particularly in the long approach marches.

Against the few organized positions, the usual missions of preparation, support, and protection were assigned to the artillery. Even here, however, a considerable portion had to be held ready to repulse flank and rear attacks from the enemy. The lack of positions giving good observation, the absence of well-defined reference points, the difficulty of range estimation, the impossibility of visual signalling, the reduced effect of fire in the thick vegetation—all combined greatly to limit the artillery possibilities in this close country.

The artillery had much more freedom of action on the upper plateau. Batteries could be posted with observation close at hand and the mass action of battalions could be utilized against enemy concentrations and for counterbattery. Such action was rare, however. The targets were usually fleeting, requiring rapid surprise fire from individual batteries.

Adjustments were as rapid and as simple as possible. Percussion bursts were very difficult to observe in the heavy vegetation, and time fire adjustments were preferred in the wooded regions. Large brackets were sought and fire for effect delivered promptly by rapid, searching volleys at irregular intervals. The safety limits for firing ahead of friendly troops had to be increased considerably over the regulation limits.

****

The operations in Somalia began in October, 1935, and ended in the advance of General Graziani’s forces to Harrar and their junction with the northern army at Diredawa early in May, 1936. They are interesting mainly because of the significant and extensive use of native contingents and the tremendous natural obstacles overcome by widely separated forces completely dependent on long and precarious lines of communication. The enemy does not appear to have offered any serious resistance after the occupation of Gorrahei, in the first week of November.

The artillery seems to have followed the usual line of procedure for the movement and employment of pack batteries. It is interesting to find that the mule was considered “the sturdiest, most courageous, most dependable means of transport for artillery in colonial warfare.” Also of interest is the fact that the accompanying batteries which have recently been attached to each infantry regiment of the Italian army are armed with a 65/17 gun of the same model as that used in Somalia.