This post aims to describe the many aspects of the theatre of operations of the war in Abyssinia. To our lasting benefit this had been done by contemporaries at the time. Using the following detailed analysis by US Army Captain Numa A. Watson, who admirably describes many of the details particular to the Abyssinian theatre of operations, we can get a quite thorough overview of Ethiopia. With a soldier’s eye he comprehensively covers many of the aspects relevant to any military operations in Abyssinia. This evaluation was undertaken as part of a study course he was attending in 1936-37. Obviously the recently completed war would be a topic of interest for such a study and thus reflects the information available.

The documents he used reference some hard to find sources not easily available to readers today. The paper is reproduced in this post as it gives a detailed military perspective of the theatre of operations. A notable author that is missing here is Major Norman E Fiske who was a US military Observer at the time who wrote a detailed analysis of the war. Captain Watson referenced that source so I have not added any further detail beyond what he has done. I have included some additional supporting pictures, diagrams and maps to highlight aspects of the text that the author would not have had available to them at the time of writing. The essence of the document is unchanged and this post does not alter his views or opinions, which remain unchanged. The original document can be found here.

.

.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Physical Geography

General topography of Abyssinia

Rivers and water Supply

Climatic Conditions

Human Geography

Population and Social Conditions

Sanitation and Hygiene

Political Geography

Economic Geography

A Study of Critical Areas

Ports and Harbours

Railways and Road Net

Possible Objectives

Routes of Invasion

Historical Retrospect

Organisation of theatre of Operations and Lines of Communication

ITALO~ABYSSINIAN WAR, 1935-36

Physical Geography

General Topography of Abyssinia

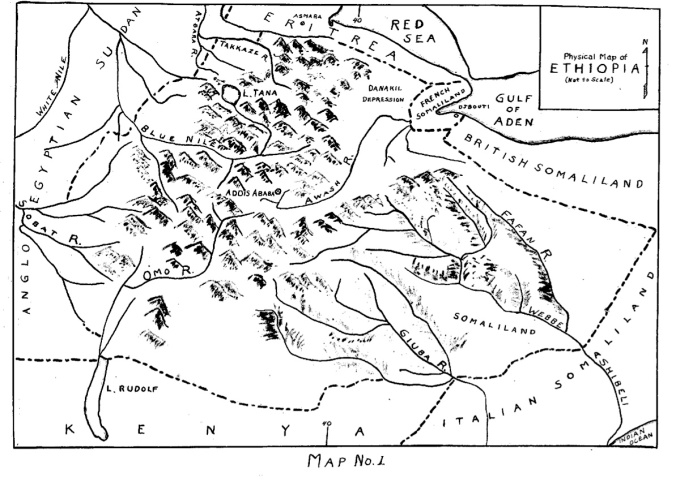

Abyssinia, officially known as “Ethiopia”, is an inland country in the northeastern part of Africa whose area is about 350,000 square miles or a little more than that of the states of Texas and Oklahoma combined. It is roughly triangular in shape. The northern portion is 250 miles wide and gradually broadens out to a maximum width of about 900 miles. It has no seaport, being separated from the Red Sea by the Italian possession of Eritrea and from the Gulf of Aden by French and British Somaliland. On the west and south Ethiopia is bounded by the Anglo~Egyptian Sudan, Kenya, and Italian Somaliland.

Between the Upper Nile and the 40th meridian is a jumbled mass of mountains and valleys with elevations rising to a height of about 15,000 feet in some places.

The general plateau level averages from seven to eight thousand feet, dropping off abruptly to the east onto the plains of the Danakil Desert in the north and, more gradually, into Abyssinian Somaliland on the south. Between these two regions a chain of smaller mountains run generally northeast and southwest—known as the Harrar Hills.

Characteristic of the mountain areas are the enormous gorges and fissures cut in the mountain sides by the erosive action of the numerous rivers and streams. Some of the valleys are quite wide while others are only a few hundred yards apart yet fall almost straight down thousands of feet.

This has caused the formation of many small flat–topped plateaus with perpendicular sides resembling a natural fort. The Danakil Depression is a hot barren desert in places as much as 300 feet below sea level. South of the Harrar Hills and east of the 40th meridian, lies Abyssinian Somaliland, a vast plateau region averaging about 3000 feet in elevation and covered with gray African brush and other scanty vegetation.

.

Rivers and Water Supply

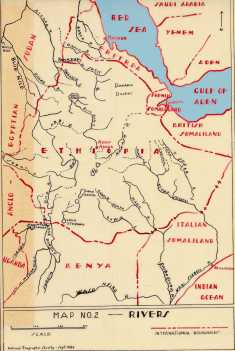

Most of the rivers drain to the northwest in the direction of the Nile. The most important are, in the north, the Takkaze; the Abbai or Blue Nile in the center; and the Sobat in the southwest. These rivers carry about four–fifths of the entire drainage of the country and supply ninety–five per cent of the water which flows in the Nile below the mouth of the Atbara.

Most of the rivers drain to the northwest in the direction of the Nile. The most important are, in the north, the Takkaze; the Abbai or Blue Nile in the center; and the Sobat in the southwest. These rivers carry about four–fifths of the entire drainage of the country and supply ninety–five per cent of the water which flows in the Nile below the mouth of the Atbara.

At the head of the Abbai lies Lake Tana with a drainage area of some 5400 square miles. an unhampered flow of water from this watershed is essential for the supply of the Nile and the life of Egypt. The rest of the drainage is carried off by the Awash to the east and north; by the Webbe Shibeli and the Giuba in the southeast and the Omo into Lake Rudolf on the south.

All these streams are perennial rivers and, in the mountains, often torrential in character. Away from the river systems and the Danakil Desert water can generally be found in existing wells or can be procured by digging at no great depths.

.

Climatic Conditions

Over such varied terrain it is natural to find similar variations in climate. In the uplands the climate is healthy and bracing in the summer time, the temperature ranging from 60 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

Winters are quite cold. In the lowlands climate is hard on Europeans. The extreme heat and high humidity cause sunstroke and heat exhaustion. Malaria is prevalent. In Somaliland the climate is dry and healthy all over the plateau.

Temperatures vary from 60 degrees early in the day to about 100 in the afternoon. In Ethiopia winter lasts from October to February. It is followed by a hot dry period until the beginning of the rainy season in June.

This begins in the north, lasting until September, and gradually moves southward.

However, in many parts of the country, the rainy season does not materialise- rains may occur at any time and their effects be quite local. Military operations are not held up uniformly throughout the region. They may be interrupted or hampered for a few days at a time but are not necessarily halted everywhere at the same time.

.

.

Human Geography

Population and Social Conditions

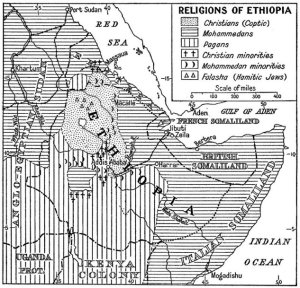

The population of Ethiopia is estimated at about ten million consisting mainly of the Abyssinians or Amhars, the Galla and the Soma1i-all African races. Among the non–Africans are numerous Armenians, Indians, Jews, and Greeks, and small colonies of British, French, Italians, and Russians. Most of the natives are distinctly negroid in appearance probably due to the number of negro women brought into the country in the old days. Due to differences in racial characteristics and religion, the Ethiopians are not a homogeneous people. The Abyssinians, or Amhars, who comprise about one-third the entire population are the ruling class. They have been able to dominate the other tribes to a point almost amounting to slavery.

The Abyssinians profess to a crude form of Christianity while the other races are strictly Mohammedans. This difference in religion, added to the mutual hatred existing between the ruling tribe and their subjects, make it difficult to estimate the fighting value of the Ethiopian army. There is nothing resembling a national military organisation as is commonly found in modern countries today.

The numerous native tribes, fighting under the leadership of their individual chieftains, or Rases, usually combine against a common foe. However, because of class hatred, very little influence is necessary to break this unity. As an individual, the Ethiopian is a strong, fearless fighter, who can withstand the hardships of moving warfare without the necessity of an elaborate supply system.

His requirements are few and simple enabling him to live off the country. Although comparatively undisciplined he will, when properly led, dash to the assault in order to close with the enemy and kill him in hand—to-hand fighting. He is, on the other hand, quickly and easily discouraged on meeting with defeat. No defensive actions or orderly withdrawals are made; individuals simply scatter to the four winds when vigorously pursued. .

.

Sanitation and Hygiene

Ethiopian dwellings are of the most primitive type. Stone and mortar are used in building but the usual home is a circular hut thatched with grass and crudely made. Inner Walls are plastered with clay, cow dung, and chopped straw. There are no fireplaces nor chimneys so that interiors are black with soot from the open fires. There is no drainage nor are there sanitary arrangements of any kind. Many of the inhabitants live in caves. Conditions in the cities are not quite so crude.

.

Political Geography

Government is based on three factors-religion, feudalism, and slavery. The Emperor, or Negus Negusti (King of Kings), who claims to be the direct descendant of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, attempts to rule the various tribes through their individual chieftains. These lesser kings possess armed bands of their own who are frequently at war with one another or with the Negus himself. In 1907 a cabinet was organised somewhat on European lines, however, its powers are probably no greater than those of similar organisations in a few European nations at the present time.

.

Economic Geography

The principal industries are agriculture and cattle raising but production barely exceeds home consumption so that very little is left for export. There are no manufacturing or industrial enterprises worth mentioning. The principal imports are salt, cotton fabrics and hardware. The total value of the foreign trade amounts to only about twelve and half million dollars annually.

With proper exploitation and modern methods of irrigation and farming, Ethiopia could produce many articles of a tropical agricultural type such as rubber, sissal, coffee, tea, cotton, and tobacco. Certain portions of the country will also produce wheat. The cattle industry which now produces only hides could be made profitable due to abundant grazing lands in some sections. Oil and ores of the following minerals have been found: gold, silver, platinum, iron, zinc, copper and coal-to what extent they can be made available future exploitation only will disclose.

.

.

A Study of Critical Areas

Ports and Harbours

The Italian possessions of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland will be considered in this discussion. Since Ethiopia has no coast line and, as long as France and Great Britain remained friendly with the Abyssinians, Italy was forced to use the ports and harbours provided by its own territories as bases for operations.

In Eritrea the best seaport is Massaua. It has a good natural harbour well protected by islands but limited docking facilities prior to the beginning of operations. The only other port of importance in Eritrea is that of Assab.

Due to the impassibility of the Danakil Desert intervening between it and the interior of Ethiopia, it would be of value mainly as an air base. In Italian Somaliland there are numerous ports but none suitable as a base for extensive

operations. The largest town and the one most favourably located with respect to the interior is Mogsdiscio. Shipping facilities are very crude- a small breakwater permits the movement of very small boats and lighters to shore but ocean going vessels must remain from one to two miles out to sea and discharge their cargos by lighters. This is a difficult operation during the monsoon period extending from May to September. The town is fairly large, modern and well built with a considerable Italian colony. The best natural port is at Dante but it is too far from the interior to be worth developing. Other ports are located at Brava, Merca, and Obbia but none of them offer satisfactory facilities.

.

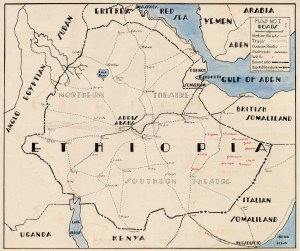

Railways and Road Net

The principal railroad in this theatre is that running from Djibouti in French Somaliland to Addis Ababa. It is Ethiopia’s only access by rail to the sea. This railroad is controlled by France allowing her to handle about two—thirds of Abyssinian foreign trade. In Eritrea a narrow gauge railroad runs from Massaua to Biscia by way of Asmara and Agordat. Prior to the beginning of operations only two or three trains made this run per week. In Italian Somaliland a narrow gauge railroad runs from Mogadiscio to Villaggio Duca Abruzzi. As far as known, these three are the only railroads in the entire war area.

In Ethiopia prior to its invasion by the Italians there were practically no roads as we know them except in the vicinity of Addis Ababa where they were of very little use to an invader. In Eritrea there were no roads capable of carrying sustained heavy motor traffic, however, from Asmara, three main roads ran generally south toward Ethiopia but ended in the vicinity of the frontier. In Italian Somaliland an improved road ran from Mogadiscio to Eelet Uen just north of the Ethiopian border.

.

Possible Objectives

In searching for a critical area as an objective for the Italian advance into Ethiopia, we find only the town of Addis Ababa with its railroad to Djibouti. There are no industrial centres, supply depots, munition plants, or similar establishments.whose capture or destruction would have any decisive effect in bringing hostilities to an end. However, capture of Addis Ababa, the capital of the country, would be a tremendous blow to Ethiopian morale in addition to cutting off her only rail outlet to the sea. Gondar and Harrar might be considered minor objectives; Gondar on account of its location with respect to caravan routes leading into the Blue Nile region; Harrar, not only being similarly located with respect to Berbera in British Somaliland, but also because it is the home town of the Emperor.

.

Routes of Invasion

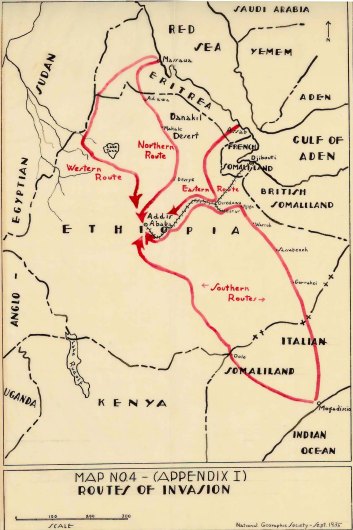

In considering routes of invasion of Ethiopia with the seat of government at Addis Ababa as the ultimate territorial objective, it is necessary to first look at the possible bases for such an expedition. We have already found that the only port deemed feasible upon which to base a force of any size were at Massaua and Assab in Eritrea, and, in Italian Somaliland, Mogadiscio, Brave, Merca, and Obbia. The railroad from Massaua to Asmara and the existing roads from that point toward the Ethiopian border seem to have provided the Italians with a running start in that direction.

However, difficulties would soon be met once the frontier were crossed; the jumbled mass of mountains, ridges, ravines, and streams traversed only by mule track and defended by native tribes who knew every inch of the country would serve to make this route an extremely difficult one. In considering Assab as a base of operations we find it situated somewhat closer to the ultimate objective yet the scorching heat of the Danakil Desert and its great extent, without roads and without water, provide an almost unsurmountable barrier to an advance of any appreciable force from this direction.

By the expenditure of considerable time, money and labor, the ports mentioned in Italian Somaliland might be made the base for an invasion of Ethiopia from this direction aimed at Addis Ababa and the railroad. The main difficulty here, aside from the poor shipping facilities, would be the extremely long line of communications to be maintained. These towns are about 200 miles from the border with from four to six hundred miles of barren arid country yet to cross.

.

Historical Retrospect

On the 3rd of May 1889, Menelik II, Emperor of Ethiopia, signed a friendly treaty with Italy, known as the Uccialli treaty, definitely fixing the boundary between Abyssinia and Eritrea, Certain terms of this treaty provided that Menelik should conduct all his foreign affairs through the Italian Government thus resulting in what amounted to an Italian protectorate over the country. A dispute soon arose between Menelik and the Italians as to the interpretation of this clause; War followed. An Italian force of about 13,000 men under Colonel Baratieri took the field against Menelik’s army of 90,000. Due to misinterpreted orders and lack of knowledge of the country, the Italian force was practically annihilated at the battle of Aduwa, 1 march 1896.

.

Organisation of Theatre of Operations and Lines of Communication

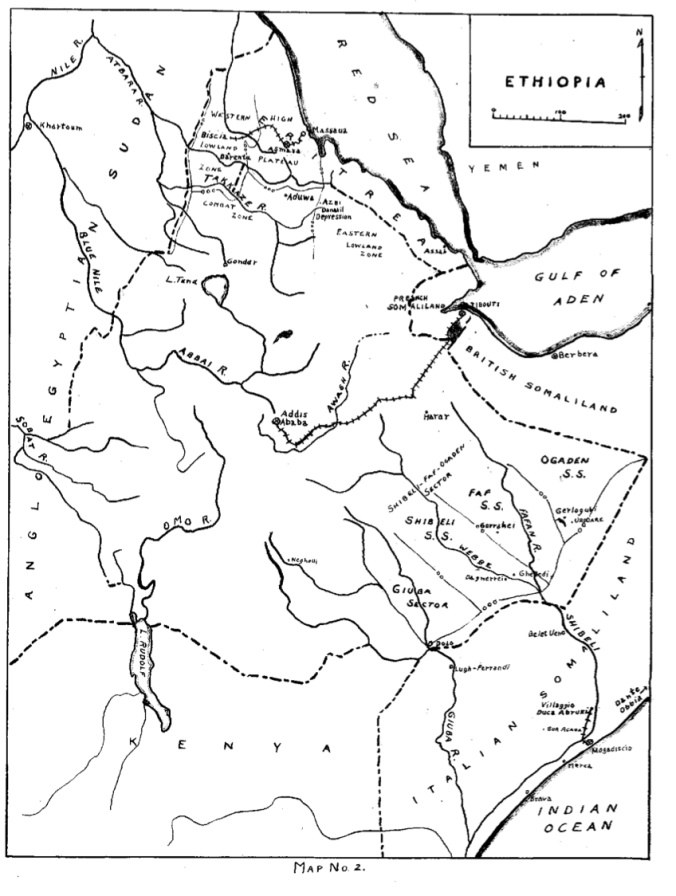

There were two main theatres of operation, the northern and the Somaliland. In the northern theatre the communication zone was divided into three parts: the centre one, known as the High Plateau, being the most important since the principal lines of communication passed.through this area. To the west of the High Plateau zone was the Western Lowland zone with headquarters at Barentu.

Until April 1956, the mission of the trosps in this area had been mainly a defensive one, which was the protection of the right flank and communications

of the troops making the main effort in and south of the High Plateau. Subsequent to this time, additional troops were brought in and an advance made to Gondar. To the east of the High Plateau was the Eastern Lowland zone of which the Danakil Desert comprised the major part. Headquarters was located at Azbi on the edge of the High Plateau. The troops in this area had a similar mission of protecting the left of the main advance. A detachment at Assab protected the air base at that point.

The Somaliland theatre was subdivided as shown on Map No.2. The principal base port and location of GHQ was at Mogadiscio. The area was organised into two sectors, the Giuba sector and the Sh1be1i—Faf—0gaden sector. Troops in this zone were mainly on a defensive mission prior to April 1936. Headquarters of the Giuba sector was at Dolo. The mission of the troops here was to protect the upper Giuha, the supply base at Dolo, and the airdrome at Lugh–Ferrandi.

An advanced base was established at Neghelli but no effort was made to maintain a line of communication to that point.

The sector to the east was divided into three subsectorg the Shibeli, the Far, and the Ogaden. The Shibeli subsector was of very little importance, its garrison being charged with the protection of the upper Shibeli and the left flank of the troops in the more important subsector to the east. The Faf subsector was the most important one on this front being the advanced base for the movement on Harrar in May 1936.

Still further to the east was the Ogaden subsector, important only for the group of wells located in the area. By occupying and defending the Gorrahei and Gherlogubi group of wells and the towns of Dagnerrei, Gheledi, and Dolo, it was felt that no Ethiopian advance could be made without a direct attack due to the lack of water.

In Eritrea shipping facilities at the base port of Massaua have been greatly improved. By April 1936, a dock 800 meters long which would accommodate from three to five transports had been built and traveling cranes and other machinery installed. Large storage depots for gasoline, oil, ammunition, subsistence and engineer supplies were constructed and stocked in this area. A cable carrier line was erected from Massaua to the High Plateau which handled about 600 tons daily. The railroad to Asmara was taken over by the Military Transport service on the opening of operations and soon ran seven trains per day of six or seven car: each, handling another 600 tons per day.

As troops advanced in the combat zone, seizing important tactical localities, they halted and dug in so that communications could be maintained. Supplies were then moved forward by bounds from base port to depots and thence to advance depots. The initial stage of road building was done by combat troops as they advanced and the work carried to completion by civilian contractors employing civilian laborers. These workers had to be protected against the attacks of raiding bands of Ethiopians. Combat troops were often specifically detailed for this purpose and lines of communication guarded by small forts along the routes prepared for all-around defense and wired in.

The complete road net as in effect at the end of the campaign in the northern theatre is shown on Sketch No. 1. Roads in the Somaliland theatre were somewhat easier to build-in dry weather it was only necessary to clear away the brush. By March 1936, roads had been constructed from Mogadiscio as far as Dolo to the northwest and Gorahei to the north. Another road had been completed from Obbia to Uardere and from Brave to Bur Acabe. Italian operations in this theatre were universally successful due to their advantage in mobility over the Ethiopians, whereas, in the north, the advantage was with the natives permitting them to hold up the advance of four modern army corps for several months.

Roads in the Somaliland theatre were somewhat easier to build-in dry weather it was only necessary to clear away the brush. By March 1936, roads had been constructed from Mogadiscio as far as Dolo to the northwest and Gorahei to the north. Another road had been completed from Obbia to Uardere and from Brave to Bur Acabe. Italian operations in this theatre were universally successful due to their advantage in mobility over the Ethiopians, whereas, in the north, the advantage was with the natives permitting them to hold up the advance of four modern army corps for several months.

The military engineers were responsible for signal communications in East Africa except radio from Asmara, the headquarters of the S.O.S to Rome, which was handld by the Navy. Radio communication was maintained between GHQ and each corps, the lowland zone commands, outlying detachments and GHQ of the southern theatre; otherwise its operation was normal.

Sketch No. 2 shows a wire diagram of the telephone and telegraph set-up in the northern theatre as of February.

Field wire was first installed on wooden poles but this was rapidly replaced with copper wire on steel poles set in concrete. Initially considerable trouble was encountered in some places due to ants destroying the wooden poles and also due to giraffes carrying away thefield wire which had been strung too low.

.

Conclusions

1. Italy considered Ethiopia’s large land area, with its great undeveloped resources, a necessary acquisition regardless of world opinion.

2. Italy’s selection of the route of invasion from Eritrea south to her territorial object, Addis Ababa, was the only practicable one available to her.

3. Ability to install and maintain lines of communication will govern the rate and extent of an advance of a modern army.